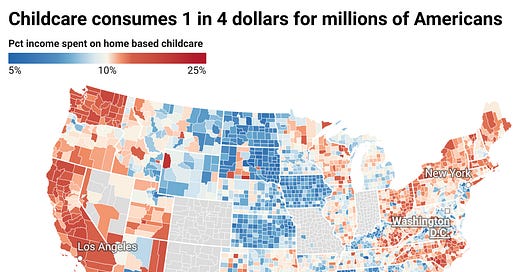

Childcare costs skyrocket in the Northeast and West

New data highlights inequalities for communities struggling with affordable childcare

INTERESTING ON THE WEB

🎉 I wrote an op-ed in TIME this week on the 5 solutions states can adopt to improve life expectancy - TIME

👀 Paul Krugman and David Wallace-Wells both cited our work in their NYTimes op-ed’s last week - Krugman’s op-ed and Wallace-Wells’s op-ed

⭐️ The LA Times did a big write-up on our work and published it in print too - LA Times

🚀 Our life expectancy map went semi-viral on the web - Twitter

🚨 New article in Nightingale, the journal of the Data Visualization Society, on how data viz can drive social impact - Nightingale

President Biden signed an executive order yesterday aimed at making childcare more affordable and accessible. This comes at a critical time when rising childcare costs have stretched families to the breaking point. But does the order go far enough?

Childcare is costing America. Millions of Americans are now spending more than 1 in 4 dollars of their income on childcare, reducing their ability to pay for housing, healthcare, or healthy food. This is particularly challenging for low-income Americans who may already have restricted budgets.

The Department of Labor (DOL) for the first time ever has just released county-by-county data on childcare spending. The DOL found that higher childcare costs remained a barrier to maternal employment in areas where care was more expensive.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services considers childcare “affordable” if it costs less than 7% of a family’s income. Nearly two-thirds of parents, including 95% of low-income parents, spend more than that. Childcare, by all measures, is largely unaffordable. Only 2% of counties with available data are actually within this 7% limit.

While childcare costs are high nationally, regions like NY and MA struggle the most

NATIONAL 🇺🇸 - Across America, average in-home childcare costs were $694 per week. This means that if a parent hired a nanny or babysitter to watch after their child, they would be spending more than $36,000 per year. This is already a whopping sum. But some communities in particular face much higher costs with much lower incomes.

STATE 📍- Massachusetts has the most expensive out-of-home childcare of any state in America, costing $20,913 annually or 64% more than in-state college tuition. For example, a parent will spend more on daycare than they will for in-state tuition for UMass Amherst ($14,718 in 2022, which is one of the more expensive in-state programs).

In 34 states, the price of childcare for a center-based program is more expensive than in-state tuition at a public university. Many parents are thinking about saving for the child’s college without realizing that the first four years of their child’s life may actually be the much more expensive ones.

COUNTY 🏡 - Our research found that residents of Bronx County in New York City have to pay 47% of their household income on out-of-home childcare for one child, the highest of any county in America. This happens despite the fact that NYC is home to America’s largest publicly funded childcare system for low-income families. In 2017, the Bronx had 3,358 regulated childcare programs. By 2022, there were 2,827 left due largely to Covid challenges in keeping childcare centers open. These closures have contributed to increased childcare prices while household incomes have not meaningfully increased.

In fact Brooklyn, Bronx, and Queens are 3 of the top 5 counties for highest percent of income spent on childcare.

Women face the greatest inequality when it comes to childcare

The high cost of childcare creates inequalities, particularly for women. A 10% increase in median childcare prices was associated with 1% lower county-level maternal employment rates. This was not the same for men. 2 million women have not rejoined the workforce since the start of the pandemic, with 90% of these women citing high costs of childcare as a reason for exiting the workforce.

In a new report titled “New Childcare Data Shows Prices Are Untenable for Families,” researchers found that maternal employment decreases in areas with more expensive child care, even in places where women’s wages are higher. A 10% increase in median childcare prices was associated with 1% lower county-level maternal employment rates.

Trend over time: Rising costs

Childcare costs have only increased over the last several decades. From 1970 to 2000, childcare costs doubled. As more women entered the labor force during this period, the demand for childcare increased. This is because historically women had adopted this childcare role in two parent households. But as America changed for the better, there was new need to watch over the children with both parents out. The unpaid work of being a stay-at-home parent got transferred to paid laborers, which actually got captured in the economic data.

Families living in poverty have felt these rises most deeply. More than 60% of families living in poverty have to forego working to stay at home to care for their children or have a family member come and provide unpaid care for their children. When families can afford childcare, it consumes a huge portion of their income, making it harder for them to rise out of poverty.

However, recent childcare costs have also skyrocketed. Since the start of the pandemic in 2020, childcare costs have increased 41%, largely as the supply of care professionals decreased due to health risks as well as these workers being overworked and under-compensated.

Childcare costs have risen faster than inflation. If your household wages did not rise with inflation, then the cost of childcare felt particularly painful since it was as though you were making relatively less while prices still went up.

Who cares for the children of childcare workers?

We also often forget about how childcare workers have their own kids who need taking care of. Jasieth Beckford, who makes $22/hr taking care of a 10-month old in NYC, started nannying when her own son was 3. “If I’m a nanny,” she says, “how am I going to afford a nanny?” When her son reached kindergarten, Beckford paid a retired grandmother $60/week. She occasionally had to pay in groceries or sandwiches when she had no other option.

Failure to capture the value that stay-at-home parents generate is an injustice to the work that parents do and dramatically underestimates GDP. This particularly devalues women who are disproportionately represented in at-home childcare work. In the early days of measuring trying to measure a country’s product, Phyllis Meade in 1941 advocated for including women’s home labor in national accounting. She spent months going to British colonies to measure and capture this data. Her colleagues rejected her suggestion, and those same colleagues later went on to win the Nobel Prize for creating a system of accounts for properly capturing country production.

It’s important to note that the supply of childcare workers has also not gone back up as the effects of Covid have waned. Childcare workers make an average of $12 per hour. It’s estimated that there were 100,000 childcare worker jobs lost during the pandemic.

The Path Forward

America is unique in how little it dedicates towards publicly funding childcare. Currently, the United States government spends just $500 annually per child on early childhood care. Comparable wealthy countries spend $14,436 annually per child on care. However, several steps can help reduce the impact of childcare and inequality for families most in need.

💰 Federal fund childcare centers: In 1943 as men shipped off to war abroad and women jumped in to run factories in the U.S., Congress passed the Lanham Act to fund day care centers with federal and local dollars. That year, families paid 50 cents per day for childcare, or equivalent to $8.69 a day now. In an Atlantic article from 2015 titled Who Took Care of Rosie the Riveter’s Kids? Raina Cohen explains that this was the first and only time in American history when parents could send their kids to federally-subsidized daycare regardless of income. The Lanham program substantially increased maternal employment and had strong positive effects on child well-being, even five years after the program ended. The U.S. should pass a peace-time Lanham Act again to reinvigorate these gains.

🎭 Offset losses when rolling out universal Pre-K: Despite the tremendous benefits for education opportunity that universal Pre-K offers, these programs actually hurt most childcare centers. Caring for children aged 1-2 is much more expensive than caring for children aged 3-4 due to teacher ratios often required by states as well as the capital costs of diapers, food, and resources required. Programs that include the full early childhood age range of 1-4 effectively have the cheaper 3-4 year old students offset the costs of the 1-2 year olds. When Universal Pre-K takes away the 3-4 year olds, schools need to manage these higher higher expenses. In Illinois, universal pre-k was found to be responsible for the closing of 610 childcare centers in a 5-year period. States can offer subsidies to these younger childcare programs to help them keep their doors open despite taking away some of their clientele.

🎟️ Employer rebates for daycare: 71% of the labor force is made up of parents and employers need to do more to support their staff. Instead of providing daycare directly to parents, employers ought to provide rebates for daycare instead. The reason for this is that employer-sponsored insurance has a history of creating job lock and can reduce job mobility by 25%. Learning from the lessons there, rebates instead can allow parents to get more affordable childcare, while also allowing them to move jobs and still keep their kids in the same programs. Studies have found proven benefits of childcare subsidies for employee retention and satisfaction.

Affordable childcare is good policy. When parents cannot get affordable childcare, it negatively impacts parental employment, which negatively impacts a region’s economic growth. American businesses lose $12.7 billion annually because we cannot get great labor force participation among women because childcare workers can’t make a living wage, and employees struggle with childcare.By some estimates, the total cost of lost earnings + lost productivity + lost revenue due to the child care crises totals $57 billion each year. For a nation that talks so much about families as being the backbone of society, we need to do more to make sure that these parents and children alike can thrive.

Special thanks to James Bradley for helping me track down this data.

What has childcare been like for you? Tell us your state or county and a little bit about you've been experiencing

Finding and paying for childcare is the unspoken burden of our generation. In Boston suburbs before COVID, our small in home center was 700/week for a toddler and a infant. They were closed most of COVID and reopened for 900/week for those same two kids. We moved to the suburbs of Chicago in late fall of 2021. Fast forward to spring of 2022 found out we're adding our last baby and I searched through 75 daycares in 3 towns for an infant spot for MARCH of 2023. I was looking 10 months in advance of needing care and only 3 places could confirm they would have an opening for an infant. The in home daycare here is 650/week for a toddler and an infant. I regularly tell friends/family now, if you think you may want children, start calling daycares to see what waitlists are like, how much it costs, etc. Bc you don't always have paid leave and don't get a raise for having a baby.