Food Deserts: Hidden Hunger in the Land of Plenty

44 Million Americans are food insecure. Here's how our policies are falling short

INTERESTING ON THE WEB

🇺🇸 Tim Walz really REALLY loves maps - Fast Company

🌞 How 3 million Americans used funds from the Inflation Reduction Act - solar panels win out - Heatmap News

🎲 Original Risk map from 1959 - Boardgames are cool

🏛️ If you too think about the Roman Empire, you’ll like this map - Brilliant Maps

Somehow in the 21st century, millions of Americans have no food. Lines for food banks routinely stretch for miles, millions of children go to bed hungry each night, and countless families are stuck making tradeoffs between buying groceries or paying rent. New analysis from the Association of American Medical Colleges and USDA shows that 44 million people are food insecure and 23.5 million live in food deserts. This means that 1 in 8 Americans struggles to eat daily, a significant change from 1 in 10 in 2021. The country is now facing some of the worst levels of food insecurity since the USDA first started measuring this metric in 1995.

While policies and programs exist to combat food inequality in America, these solutions have fallen remarkably short.

Food insecurity occurs when food is either too far away or too expensive to purchase. A food desert is one type of food insecurity. When a person lives in a food desert, this means that a supermarket is more than 1 mile away in an urban area or more than 10 miles away in a rural area. This can be manageable if your family has a car, but 2.1 million Americans live in food deserts and don’t have a car or public transportation on top of that to get to a supermarket, making it nearly impossible to achieve food security.

High food prices also cause food insecurity. If you live in one of America’s many rapidly gentrifying neighborhoods, you may have seen a Whole Foods pop up. While some have playfully rebranded Whole Foods as “Whole Paycheck,” the costs at these types of supermarkets can be ruinous for families that can’t afford to shop there, especially if other more affordable grocery stores get pushed out. This means that a low-income family living in a region of high-priced grocery stores effectively lives in a food desert.

Jefferson County, Mississippi is the most food insecure county in America. 1 in 3 people there is food insecure. Jefferson County also has the lowest median household income of any county in America at $20,188. The 8,000 families that live here are caught in a vicious cycle of food inequality — they live miles from nearby groceries, and even when they can make it to the supermarket, they can’t afford the healthier food options. They turn their cars around and go to fast food chains that are cheaper or closer to home. Life expectancy in Jefferson County is 5 years lower than the national average.

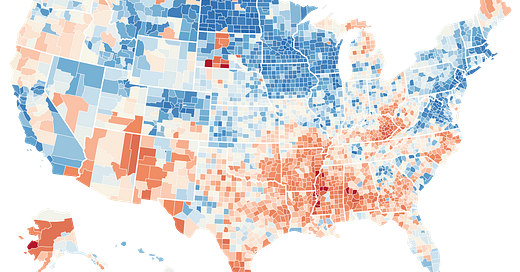

Food insecurity is dominant in the South, but it perseveres in the Midwest and Southwest too. For example, The Dreier family in Mitchel County, Iowa struggles desperately with food insecurity every day. When National Geographic interviewed Christina Dreier in 2013, she explained how she often has to send her three year old son, Keagan, to school without breakfast, hoping that he’ll eat the school’s free lunch. If Christina decides to get groceries during the week, she ends up working fewer overtime hours at her job, which means less money for food overall. As a loving mother, Christina often forego meals for herself to make sure that Keagan has enough hot dogs or tater tots to eat. Taking matters into her own hands, Christina planted a vegetable garden in her Iowa backyard, but it doesn’t produce nearly enough for healthy living.

The average low-income family spends 2 out of every 6 dollars they get from income on food each year, and another 3 out of every 6 dollars on rent, which doesn’t leave much left for internet payments, car payments, medical bills, or diapers for babies. Food insecurity is the USDA’s way of capturing these tradeoffs.

Groceries sold in food deserts are often far more expensive than those sold in cities or suburban areas. For example, milk prices in food desert tend to be 5% higher and cereal prices 25% higher. This is because getting the food to the regions in the first place can be expensive, leading to higher shelf prices that get passed on to consumers. As noted above, For low-income families, this means that they often spend a larger percentage of their paycheck on food, creating a vicious cycle of food insecurity.

Deserts and Demographics

Food insecurity does not hit all Americans equally — race is a dominating factor. Black families are twice as likely to be food insecure as White families, with 19.1% of Black households and 15.6% of Latinx households experiencing food insecurity in 2019 compared to 7.9% for White families. This clear racial divide is often a product of underinvestment in Black neighborhoods for supermarkets, grocery stores, and affordable food options. Majority-Black neighborhoods are more than twice as likely as majority-White neighborhoods not to have a supermarket.

8 of the 10 counties with the highest food insecurity rates in the nation are at least 60% Black. 7 of those 10 counties are in Mississippi along the river.

America is a global outlier in food insecurity. 1 in 6 Americans report running out of food at least once a year. In most European countries, only 1 in 20 report the same. In addition, the increasing rate of food insecurity is also far greater than in many other OECD developed nations. In the late 1960s, America had 9.6 million food insecure people — by 2012, this number had grown by a factor of five to 48 million.

American Obesity

While some Americans are starving, others are dangerously obese. Living in a food desert does not cause obesity, but it doesn’t help. Often it is easier for families to go to fast food chains than it is to get healthy groceries. 42% of American adults, or 96.6 million people, are obese according to the CDC.

Jefferson County, Mississippi is not only the most food insecure county in America, but it is also the most obese. Nearly half the adult population in Jefferson is obese. The men in Jefferson die from heart disease at a rate 20% higher than the national average.

In this Mississippi River county, life is objectively hard. Families have no supermarkets, have no healthy food options, and have such low incomes that it is hard break out of the vicious cycle that they are caught in. The county is 86% Black and voted overwhelmingly for Hillary Clinton in 2016 and for Joe Biden in 2020.

Nevertheless, federal and state level programs exist that can help those who live in food deserts or struggle with obesity.

The Path Forward

Food assistance programs do exist to help Americans in need. The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), formerly known as Food Stamps, helps 40 million low-income Americans each year receive an average of $127 per month to buy food. On top of SNAP, the National School Lunch Program (NSLP) and the School Breakfast Program (SBP) serve approximately 15 million breakfasts and 30 million lunches daily at low or no cost to students.

Nevertheless, these programs are still unable to provide enough food to the counties most at risk. The USDA estimates that families would need another $20 billion to completely eliminate the food insecurity shortfall. As such — two possible paths exist for reducing food insecurity and improving healthy living in America.

Increase the SNAP budget — Food stamps have a long history of feeding Americans. Since its inception in 1939, the Food Stamp program has helped hundreds of millions of Americans achieve food security. Every year it effectively lifts about 1% of the American population out of poverty. The most food insecure counties rely the most on SNAP. Unsurprisingly, I found there there is a 77% correlation between household income and food insecurity. An increase in the SNAP budget by 10% can reduce food insecurity for children by 22%.

Increase Access to Healthy Foods — The New Markets Tax Credit (NMTC) has been one of America’s most successful policies for encouraging new development in underserved areas. Although NMTCs are not exclusively focused on food deserts, they have helped fund the creation of over 300 supermarkets in food deserts in recent years. This would make it easier for organizations like Daily Table to spread to neighborhoods most in need. Moreover, Congress currently has a bi-partisan bill on the floor called Healthy Food Access for All Americans Act (HFAAA) which would provide dedicated tax credits to stores and supermarkets identified as “Special Access Food Providers” (SAFPs). Congress should pass this bill so that food providers wouldn’t have to compete with other development types for tax credits.

Promote healthy lifestyles through community programs - Michelle Obama’s Let’s Move! campaign helped 15 million children receive healthier meals. In addition, she was able to get commitments from 225 corporations like Walmart and Dannon to source healthier ingredients for the foods they sold. Just because the Obamas have left the White House does not mean that we need to relinquish our commitments to exercise, healthy food, and clearer food standards.

Christina Dreier and her son Keagan had their car repossessed a week after they were interviewed because they chose to eat. Food shouldn’t have to be a tradeoff for families, and this tradeoff shouldn’t fall disproportionately on Black and Latinx families. 54 million people are food insecure and 23.5 million live in food deserts as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Food is one our most basic needs - let’s build supermarkets, pass policies, and help ensure that children like Keagan don’t have to go to bed hungry.

In my red and mostly rural home state it's not uncommon to read about grocery stores shuttering and locals being stuck having to drive 45 minutes or more to have access to much more than a gas station hot dog. I'm sympathetic to the idea of subsidizing modest grocery stores or farmers' markets so people are not left high and dry.

That being said, I'd say especially in urban settings the "food desert" discourse can reflect the upper middle class cultural predilections of folks like Michael Pollan more than it does the consumer choices of local residents. There's an extent to which fresh vegetables are an acquired taste without the immediate gut appeal of greasier, saltier, crunchier, more prepackaged things, or that flavored seltzers are not as viscerally grabbing of one's taste buds as a big sugary soda or slurpee. I did some research on this for Bill Moyers, there have been a lot of cases where well-meaning philanthropists or local officials have spent a lot of money hosting farmers' markets offering produce for which there's very little actual demand. Maybe there could be better nutritional education, but people also like what they like.

One of my big frustrations as a policy major was the frequent tendency to term complex issues as anodyne abstractions it's easier to talk about. "Food insecurity" as a term kind of suggests it's just a matter of throwing more money at a single solvable problem, rather than an intractable tangle of conundrums to endlessly struggle with.

I think one of the key points is that people having trouble accessing or paying for food are likely to still get enough calories, but to do so by turning to junk food available at gas stations and convenience stores or fast food chains, all with negative health consequences. This may become a habit or behavior that is hard to change, even if food resources or availability is altered via public policy.