Homelessness and Inequality

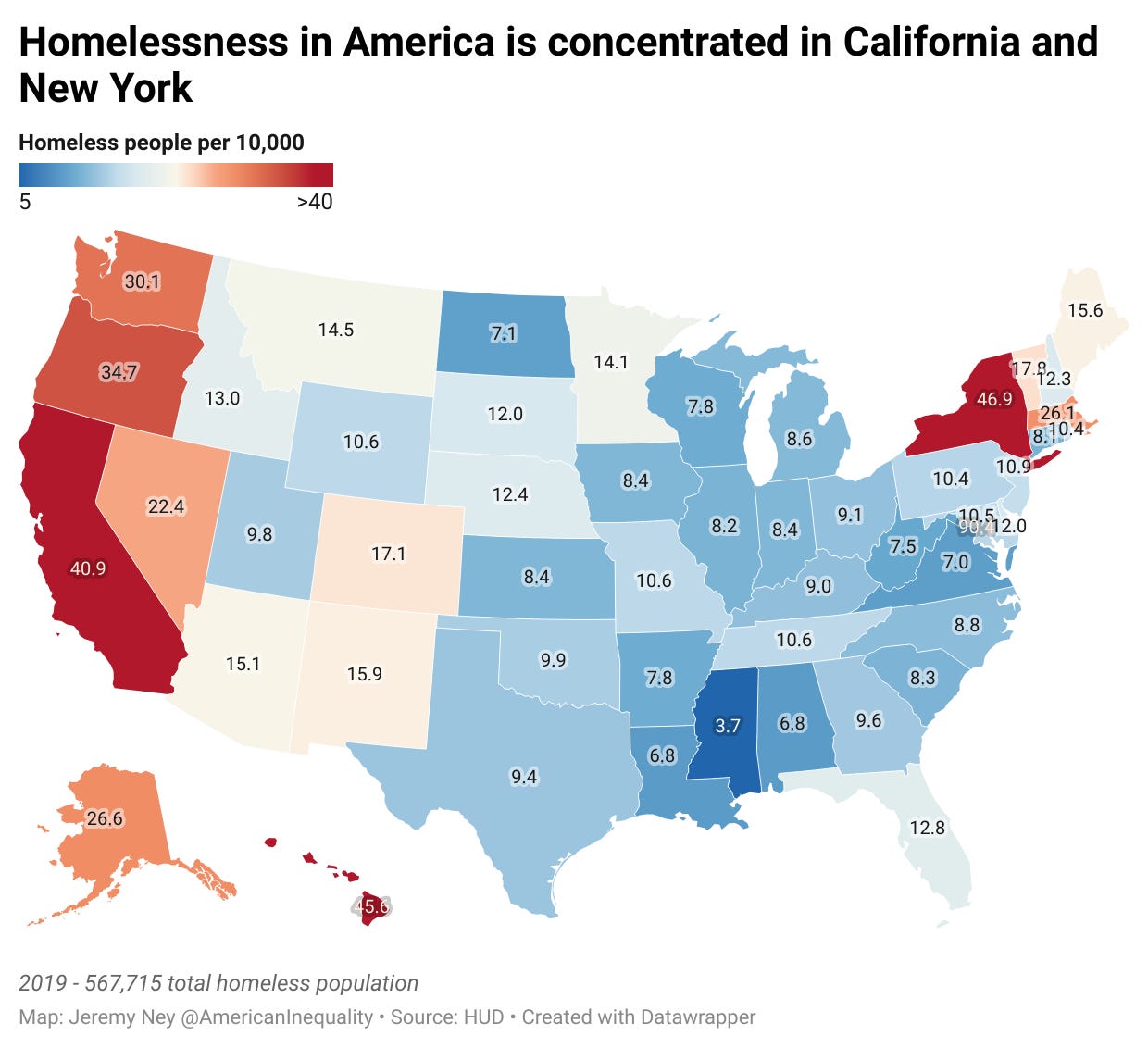

567,000 people are homeless in America - half of them live in just two states.

Karla Garcia became homeless after her dad lost his job during the 2008 financial crisis. First, the family sold everything in the house. The jewelry. The couch. The mattress. At night all her siblings would crawl into the same bed. Next, they made tradeoffs. Do we pay for gas or electric this week? Do we work an extra shift or pick the kids up from school? One day, Karla returned home from school and found the doors locked. That night, they all got into the family van and fell asleep. That routine would become their new normal. In just a few months, Karla remembers how “We went from having a normal life and stable housing, to being homeless.” COVID-19 has created countless stories like this all over again.

567,000 Americans are homeless today, and this number has been dramatically increasing. 70% of all homeless people are men, and nearly half of all homeless people live in just two states — California and New York.

New York has 91,000 homeless people, according to HUD. Homelessness in New York has emerged as the city has failed to provide affordable housing to residents and failed to build new shelters. In 2017, Mayor Bill De Blasio announced his “Turning the Tide”, but it has fallen years behind schedule. As of December 2020, only 43 of the 90 shelters are operational and 37 are sited but not yet operational. At the same time, advocates have continually criticized the mayor’s ambitious, multi-billion dollar housing program for failing to build enough apartments for very low income earners. De Blasio has created 166,000 affordable rental units since 2014, but more than half of all New Yorker City residents are still rent burdened, spending more than 30% of their income on rent, and these units are not designed for the communities with the greatest need, specifically those earning less than $20,000.

California has 161,000 homeless people, according to HUD, Homelessness in California has emerged as economic hardships have increased in the state. In Los Angeles, more than half of all homeless people cite economic hardship as the primary reason that they fell into homelessness. In San Francisco, 26 percent of the homeless cite the loss of a job as the primary cause of their homelessness. A renter in LA earning minimum wage ($13.25 an hour) would need to work 79 hours per week to afford a one-bedroom apartment.

California homelessness has also gotten worse, as long-time residents have been priced out of their homes. L.A.H.S.A.’s 2019 homeless count found that 64% of the 58,936 Los Angeles County residents experiencing homelessness had lived in the city for more than 10 years before many of them were priced out of their homes. In San Francisco, 43 percent of the homeless said they had lived in the city for more than 10 years before they too could no longer afford rent.

Drivers of Homelessness

Inequality in homelessness arises for three main reasons — financial hardship, household crises, and systemic factors.

Financial hardship — Low-income Americans are already living on the brink of financial challenges

Household Crises — Household crises like mental health challenges or domestic violence can push people into homelessness. 39% of youth experiencing homelessness have self-reported mental health problems, and homeless youth are 3x as likely to attempt suicide as housed youth. In addition, domestic violence is the most common reason women give for their homelessness. In just one day in 2015, 31,000 adults and youth fled their homes due to domestic violence, and unfortunately 7,000 were unable to find a shelter that could take them in. Addiction and substance abuse can also play a strong role in homelessness, and vice versa, the more likely we will find solutions.

Systemic Factors — 1 in 200 Black people are homeless, compared to 1 in 1,000 White people who are homeless. Systemic racial factors of homelessness can be traced to America’s long history of preventing Black Americans from owning homes in the first place. From the Federal Housing Administration’s 1934 Redlining Policies, to exclusionary mortgage practices of the G.I. Bill, to White housing covenants (see Shelley v. Kraemer, 1948), to the acceleration of White flight after the 1956 Highway Act, to the 12x difference in White-Black wealth, to the $48,000 undervaluation of Black homes on average, to the fact that Black loan applicants are consistently rejected twice as often as White loan applicants (which has been true since 1988) - all of these factors have made it herculean task for Black Americans to get a home and stay in it.

Do we even know how bad Homelessness and Inequality really is?

It is incredibly difficult to count the actual number of homeless people. HUD’s process uses a “point-in-time” count in which volunteers and organizations visit shelters and walk through neighborhoods on a single night in January to count the number of homeless people. HUD then uses this information to estimate what percent of the homeless population this number actually represents. We know for a fact that this process is imperfect. HUD’s point-in-time process counts 567,000 homeless people, but the Department of Education has reported at least 1.5 million school children, indicating massive discrepancies. This discrepancy largely emerges from definitions, since the DoE includes, “children and youths who are sharing the housing of other persons due to loss of housing, economic hardship, or a similar reason.”

Despite the logistical difficulties in counting people, there are also some policy choices that advocates make. For example, people who may be living in motels or hotels are not considered homeless according to HUD. In addition, transgender or non-binary people were only counted for the first time last year as a separate category, and we now know they represent 1% of all homeless people.

COVID-19 has exacerbated homelessness, particularly for students. When Allie Smith was just 3 months away from high school graduation, she was told that school would be closing and she would have to finish the rest of her classes from home due to the pandemic. The problem was, she didn’t have a home. Allie struggled to keep her grades up as she figured out how to connect to the internet, how to keep her camera on, and how to meaningfully stay engaged in class.

The Path Forward

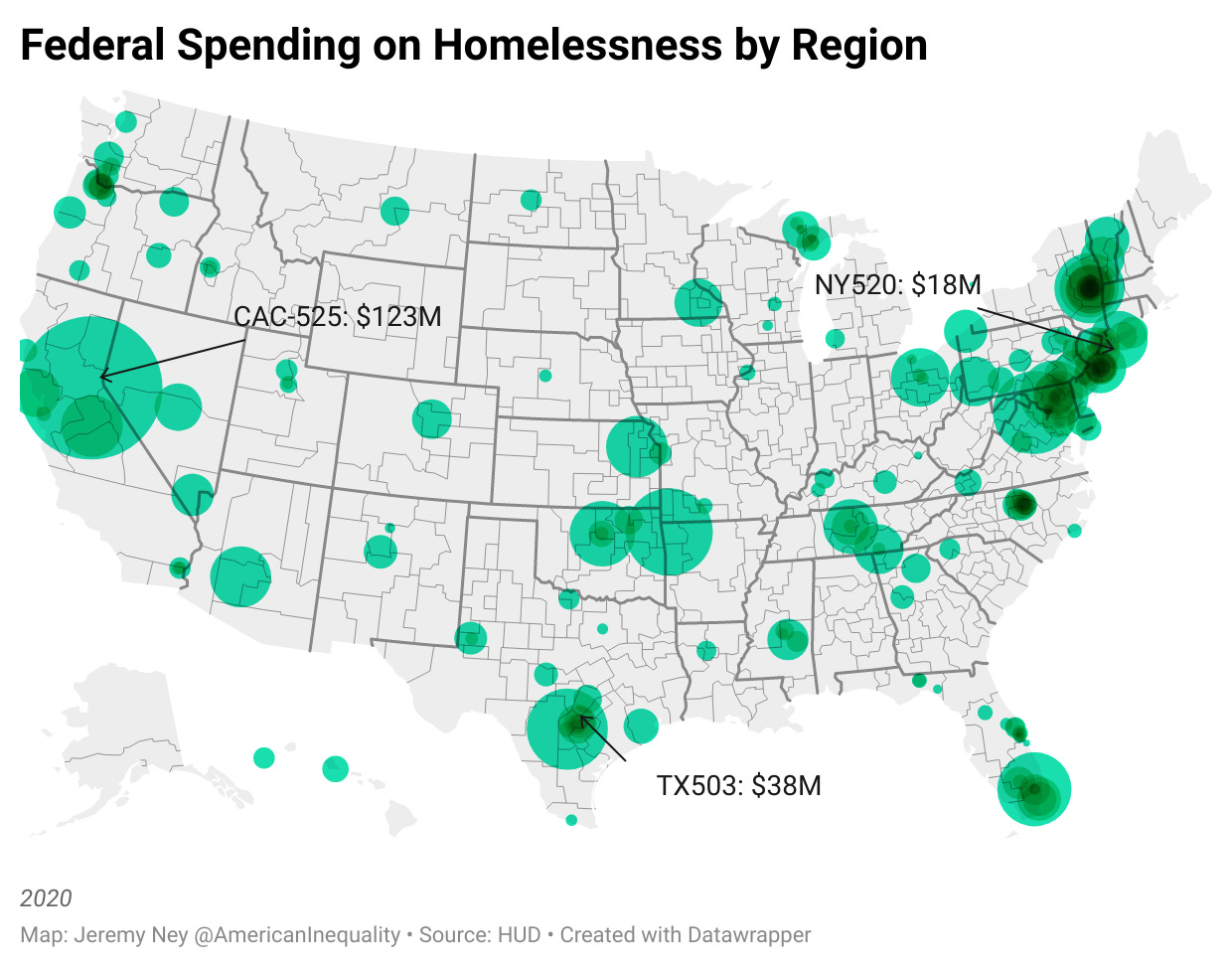

HUD estimates that it would cost $20 billion to end homelessness in the United States. PAC — Permanence, Assistance, and Crisis Readiness — is a framework for helping us get closer to this goal.

Permanence — Permanence refers to long-term solutions like finding homes for homeless people, arguing that the upfront investment can have huge gains down the road. Investments in permanence solutions have been responsible for an 8% reduction in chronically homeless families over the last 13 years and are particularly helpful for the 13% of families that return to homeless care after 30 days. The major proponents of permanence solutions argue that it only costs $12,800 per person annually for these solutions, as opposed to crisis readiness solutions that tend to cost $35,000 per person annually. The Coalition for the Homeless estimates keeping a family in their home (i.e. preventing them from ever experiencing homelessness in the first place) saves taxpayers $68,422 per year in shelter costs.

Assistance — Assistance refers to those medium-term solutions like shelters, hotels, or camp sites. There are 301,000 assistance beds for homeless people in America, but this has fallen by 9% in the last 5-years. America now has a 170,000 bed gap for people who need places but have nowhere to sleep.

Crisis Readiness — Crisis Readiness refers to supportive services for people who may be having mental breakdowns, are struggling with addiction, or need security from violence in the home. Studies have found that people who don’t take their schizophrenia medication are much more likely to be homeless as are those struggling with PTSD and those battling substance abuse. Crisis Readiness services can help families and individuals manage tremendous challenges so that they can get back to their jobs, their communities, and their lives. Executive Order 13594 was a strong step in the right direction.

These three levers won’t work alone — we need a continuum of care to adequately address homelessness.

One of my closest friends at the Harvard Kennedy School, Yasmin Serrato-Muñoz, wrote this incredibly powerful, thoughtful article in the Orlando Sentinel that captures a moment of intense reality:

Imagine. A knock on the door shatters your known world. A single word glares at you as you read your landlord’s letter: “Vacate.” The world becomes a little darker. The clock is ticking. Your time is almost up. Threats of lawyers and physical removal ensue.

Where will you go? If you are lucky, you can move in with family members. If you have some means, a long-term hotel is an option. None of the above? You can try a homeless shelter, but those are usually full. Losing your home stays with you. Trust me, it happened to me and my family 14 years ago. The memory is still vivid.

PAC - Permanence, Assistance, and Crisis Readiness - can help millions of Americans from ever having to hear that knock on the door or wondering where they will have to turn. Let’s work together to make a dent in ending homelessness.