Income Segregation and Inequality

Our first guest columnist, Esteban Moro of MIT, highlights the places in America where the rich and poor hardly ever interact

This article draws on Esteban Moro’s research that was published in the July 2021 edition of Nature. You can also view Esteban’s TED Talk on this topic here.

Traditional understanding of segregation is based on the idea that “we are where we live.” Although residential segregation is very important, the average American commutes 16 miles to work and travels more than 4 miles for groceries. Most of the people we interact with at our workplaces or social venues live far away from us. We might live in a very segregated area but, because of our work, life and habits, we may end up having a very diverse network of contacts across the main socio-demographic groups in the city. On the contrary, even if we are surrounded by people from different groups we might choose to go only to restaurants or public spaces where we only find people like us.

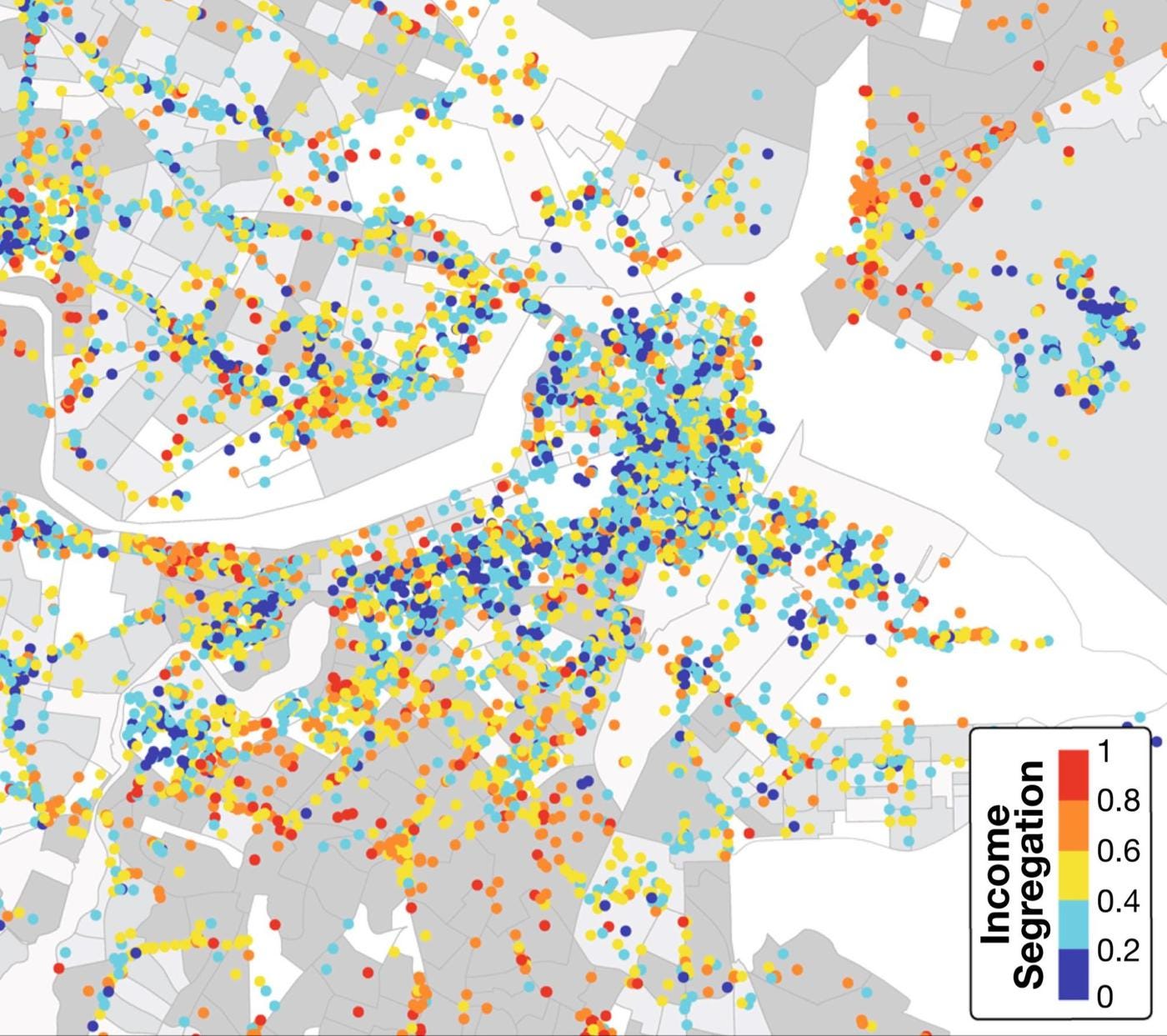

Understanding segregation beyond our residential areas is a challenge because it is difficult to capture the complex lifestyles and movements of people. However, in recent years, access to detailed mobility and visitation data to different places has permitted investigating segregation where it happens, in specific places. The “Atlas of Inequality” is one of these projects. In this work, I used aggregated anonymous location data from mobile phones to estimate the distribution of time that different income groups spend in different venues, from restaurants to libraries or museums. A very unequal place is only visited by an income group, while a diverse place is visited evenly by all incomes.

It is important to note that racial segregation and income segregation often go hand-in-hand. While more mobility research is yet to be done on this topic (i.e. the extent to which Black and White Americans visit the same locations), the focus on income segregation for this paper is critical, particularly because of the way the Supreme Court has handled cases of discrimination.

Eric Olm experiences this income segregation in a glaringly physical way. In his Lincoln Square building in NYC, Eric is a low-income resident who is forced to use a different entrance than the higher-income residents of the building. These “poor doors” ensure that richer and poorer residents don’t have to interact.

Eric looks out over the building’s courtyard, but tenants from the “poor-side” as he puts it aren’t allowed to visit there. “It would be nice to actually get to enjoy it,” he laments.

The building even gives different mailing addresses to residents. Technically Eric lives at 40 Riverside Blvd while his wealthier counterparts live at 50 Riverside Blvd.

One of these wealthier tenants didn’t see the problem - “It’s unfortunate to make it into a class warfare. It’s not us against them.” However, the resident, who requested anonymity, admitted he had never mingled with his less-fortunate neighbors.

NYC passed a law in 2015 disallowing poor-doors, though many argue that the practice still persists.

Which places have the most income segregation?

Segregation within even one block is unfortunately common.

One of the key results found in the Atlas of Inequality is that some types of places are more segregated than others. On average local shops are more segregated by income than museums, art venues, or airports. Factories are more segregated than offices. Certain types of restaurants are more segregated than others.

The least segregated places by income in America are science museums. People from all walks of life come to science museums to experience the exhibits in all their wonder.

But there is large spatial variability, to the extent that two coffee shops in the same block (or even the same street) are visited by very different people, resulting in being more or less diverse. As a result, segregation happens even at the street level. And f for Eric, this can occur within the same building.

The Path Forward

Our results show that some places are more segregated than others. What can we learn from these less segregated places? Does our neighborhood or the city center need another coffee shop? Will it attract more diverse visitors? Or only the people living in the area? If resources are limited, is it better to build a public space like a park or a library? The data provides more insights on how we can reduce income segregation.

Encourage city development of diverse places - We know that science museums and certain types of eating establishments encourage people from different socioeconomic brackets to come together. Cities can encourage development of these types of institutions. For example, my team and I analyzed a major opening in downtown Boston of a famous Italian restaurant and big store. We found that this opening increased the diversity of people visiting the area by 15% (controlling for other factors in the city and neighborhood). We have also found significant effects by malls closing down, new parks, or particular events like closing down streets to traffic and opening them to recreation.

Change your daily routine - If you realize that everyone at your Blue Bottle Coffee doesn’t even blink at an $8 coffee, maybe you should try a different story. Income segregation doesn’t just happen where you live, it happens in every place we go. Just deciding to have coffee in a different spot across the street will impact the customers we see and lead to more interactions with people from alternative economic groups in the city. It’s that simple to increase the diversity of the people in our small villages. You might say: “I’m too busy to do that” or “even if I do it, will it have any real impact on me?” Yes! Our data shows that by changing just 1% of your day-to-day habits about what places you choose to frequent, positively changes the composition of your small personal village by 5%, yielding to a decrease in your segregated encounters.

The Atlas of Inequality is a powerful tool to understand how this is happening today, but the methodology can be extended to monitor changes in the area and see the impact of new venues.

The extreme case is what happened during COVID19 lockdowns. That massive change of behavior completely altered the diversity of our interactions. We have never been so segregated as when we stayed home.

The bad news is that in the new normal people are still working at home and shopping online, decreasing the chances to interact or encounter other people. So the experienced segregation in our cities has increased tremendously, specially in urban areas.

The good news is the pandemic has brought the possibility to create new or redesign old recreational, walking, shopping spaces. This could be an opportunity to revamp our social fabric in our cities.