The American Loneliness Epidemic

Male loneliness and the Man-o-Sphere are just the tip of the iceberg

Scott Galloway and Liz Plank had a brilliant conversation about male loneliness that went viral. When Galloway argued that we often tell men to ‘fix their problems’ — something we’d never say to a Black person or a woman — Plank had to push back.

“The reason why women expect men to do something about their problems is that they’re not powerless. In fact, now more than ever, they are in charge. That doesn’t mean we should lack empathy for their pain, or patience for their learning. But the tacit request that women now solve this problem for them, as we’ve been asked to solve so many others, is not just unproductive. It’s offensive.”

As far as the data goes, America is experiencing a crisis of male loneliness. The way we respond to this, however, is a question that has prompted fierce debate. As Plank summarized in her conversation with Galloway, “Male Loneliness Isn’t a Crisis—It’s a Mirror.”

On one hand, I tend to agree with Plank. Men are now clamoring that this is an “epidemic” while women and minority communities have been struggling with isolation and far worse inequalities for decades. Even with the “epidemic” of male loneliness, men still remain in a higher position of privilege than their peers, particularly Black women. White men with a criminal record are more likely to be hired than a Black woman without one. When women raised the flag about these concerns for themselves, where were the men?

On the other hand, I also tend to agree with Barack Obama who weighed in on the debate last week. The male loneliness crisis is very real. It creates very real threats to at-risk boys and perhaps worse, to communities more broadly.

“What we’re learning is that, when we don’t think about boys and we just assume that they are going to be OK because they’ve been running the world and they’ve got all the advantages relative to the girls — all which has historically been true in all kinds of ways — but preciously because of that, if you aren’t thinking about what is happening to boys and how they are being raised, that can actually hurt women. And some of the broad political trends that we’ve seen in this country and in the world, has to do with this sense of boys, men, feeling like they aren’t seen, as though they count, and this makes them more interested in appeals that the reason that you don’t feel respected is because women have been doing this or that group has been doing that, and that isn’t a healthy place to be.”

All of this is also occurring in the context of a growing “manosphere” (or as Obama indicates, perhaps the manosphere is preying on these insecurities). When Mark Zuckerberg says that Meta needs to have more “masculine energy”, we don’t all say hallelujah to Mark for tackling the crisis of male loneliness. We’re so worried that boys are falling behind in schools, which they are, but what about the fact that schools were never designed for women in the first place? Women weren’t allowed into Yale until 1969, Brown until 1971, and Columbia until 1983. There’s still a deep power imbalance that occurs, not the least still evident in a gender pay gap where women earn 83 cents for every dollar a man earns, but where’s the declaration of an epidemic for maternal mortality? What about the surging rates of domestic violence?. We’re so worried that all of the mass shooters in the US are male, and we find these manifestos riddled with feelings of loneliness, isolation, and getting pulled down internet rabbit holes.Yet, we focus on the boys instead of the fact that there are 512 million civilian-owned guns in America and that states with common-sense gun control have far fewer shootings.

We’re missing the forest for the trees.

Loneliness as a Public Health Problem

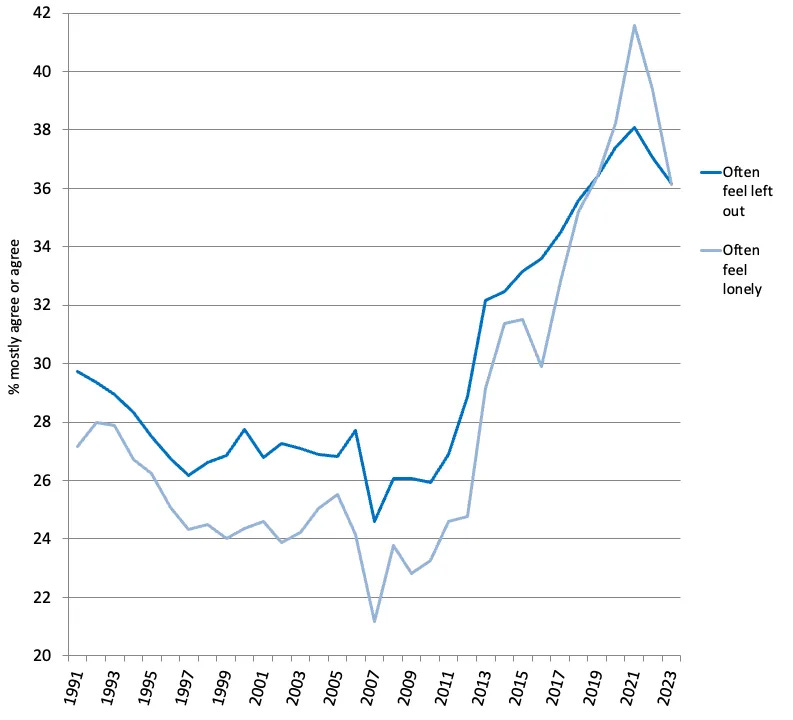

The lonely are not just sadder—they are unhealthier and die younger. Loneliness is driving alarming increases in suicide rates, worsening mental and physical health, eroding academic achievement, and deepening inequality. The effects are far-reaching, touching everything from social cohesion to labor force participation. And, the numbers are moving in the wrong direction.

A landmark 2021 survey from the Survey Center on American Life found that 15% of men reported having no close friendships—a fivefold increase since 1990. A May 2025 Gallup poll found that 1 in 4 men under 35 in the US is lonely, 10 percentage points higher than their OECD peers. A 2023 meta-analysis published in Nature Human Behaviour found that loneliness increases all-cause mortality by 26%. Former Surgeon General Vivek Murthy has warned that its impact on the body is equivalent to smoking 15 cigarettes a day. According to the CDC, men accounted for nearly 80% of all suicides in 2022.

While social isolation affects all genders, men are uniquely vulnerable: they tend to have fewer intimate relationships, are less likely to seek emotional support, and often rely heavily on a spouse or partner for their emotional needs.

Did someone forward you this email? Sign up here.

The impacts go far beyond mental health. Loneliness is correlated with higher rates of hypertension, heart disease, obesity, and alcohol use—all of which disproportionately affect men in rural and deindustrialized regions. This relationship appears in the data. In states like West Virginia, Kentucky, and New Mexico, men are reporting unprecedented levels of social isolation, with devastating consequences.

Social isolation also takes a toll on educational and cognitive outcomes. Boys and young men are increasingly falling behind in school, especially in reading and writing—skills that are often nurtured through social and emotional development. The National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) shows that since 2012, reading scores for 8th-grade boys have declined steadily, while girls have held steady or improved slightly. In higher education, men now make up just 41% of college students, down from 58% in 1970.

What is driving the rising rates of loneliness?

Sociologists have declared social media as public enemy #1 in the male loneliness crisis. One of the most definitive studies on this relationship comes from Harvard Graduate School of Education’s Making Caring Common (MCC) surveys, which found that technology was the biggest source of their loneliness, according to respondents.

In another study published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine, those with higher social media use (two hours or more per day) felt more socially isolated than those with lower social media use. Nevertheless, it isn’t exactly clear to me why social media is so much worse for men than for women, particularly when we have consistently heard that social media is incredibly toxic for teenage girls.

The second cause that people point to is the decline in social institutions like Boys and Girls Clubs, community centers, religious organizations, and bowling clubs. Our lives are increasingly being lived online and separated from each other, and while the internet can make it seem like we are always connected to everyone, the exact opposite is true. Social institutions in the real world are some of the best antidotes for loneliness.

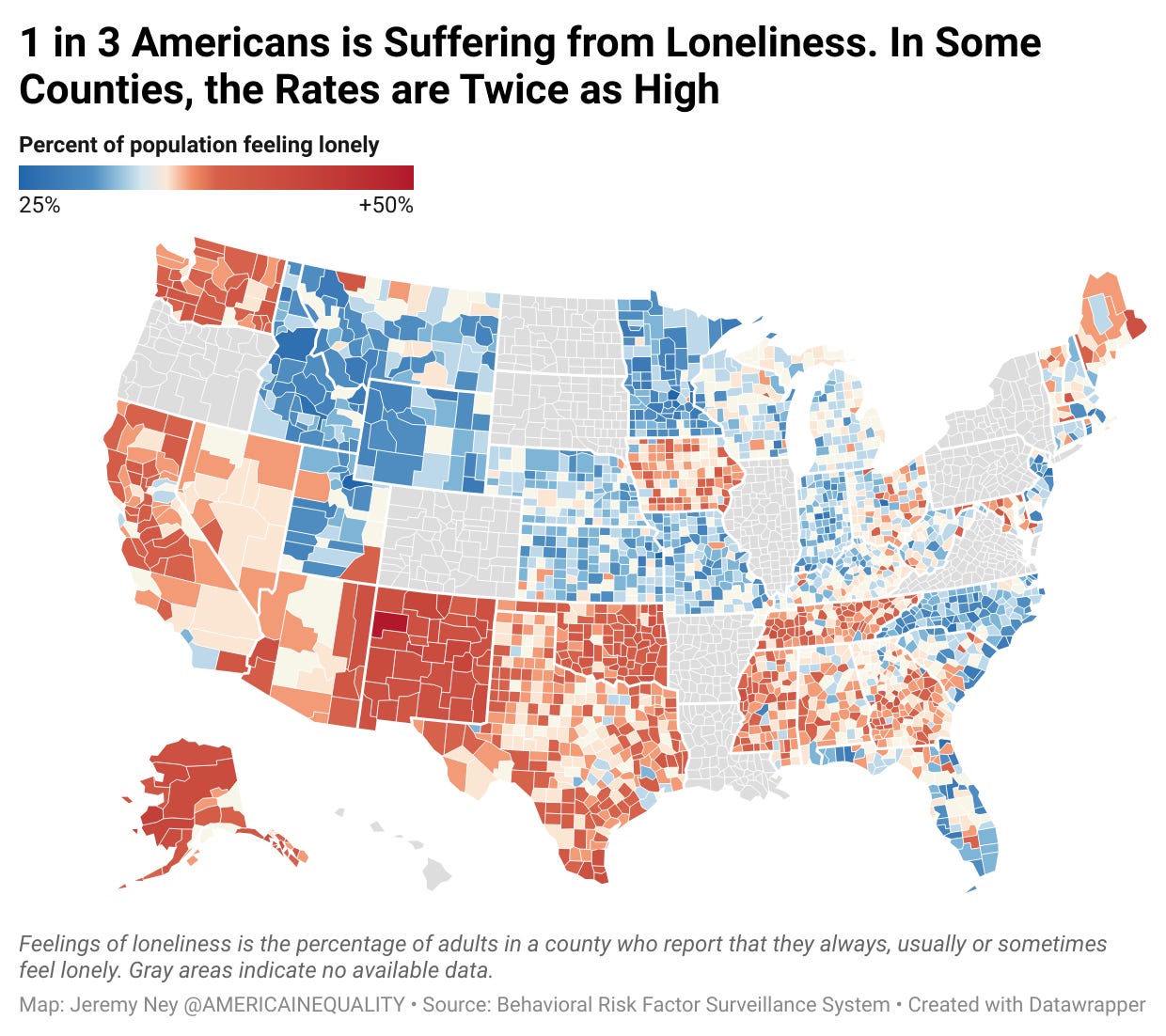

Geographically, the loneliness crisis is most acute in states with high unemployment, low levels of civic infrastructure, and limited access to mental health care. As the map above shows, not all states have begun publishing their county-level data on loneliness. McKinley County, New Mexico is the loneliest county in the loneliest state in the nation. 48% of residents there report feeling lonely. This county of 73,000 in the northwest part of the state is 75% Native American, home to the Navajo and Zuni reservations. Native Americans have the highest rates of suicide of any demographic in America. Their rates of heart disease are 50% higher. They are twice as likely to die from alcohol as any other demographic. Once again, we are missing the forest for the trees.

As

summed up in her conversation with Scott Galloway:"This isn’t about blame, it’s about responsibility. The same way we expect those with power to act in any other crisis, we expect men to do something here. Not because women can’t. But because we already did—and we were ignored. Women haven’t just asked men to help. We’ve begged. We’ve organized. We’ve explained. We wrote books. We started podcasts. We’ve softened the truth to make it palatable. We’ve screamed it raw. And in return? At best, silence. At worst, retaliation. So when men say, ‘We’re hurting,’ the response isn’t, ‘Too bad.’ It’s, ‘Welcome. Now grab a shovel.’”

The Path Forward

Build more clubhouses across the United States: Clubhouses are member-led communities that provide people living with serious mental illness a sense of purpose, connection, and support. Expanding the clubhouse model offers a powerful, cost-effective solution to provide persons with serious mental health a community. The concept of a clubhouse starts with the idea that “community is therapy.” Research by Fountain House links them to improved mental health, higher employment and education rates, and nearly $700 million in annual U.S. savings. Most importantly, clubhouses significantly reduce loneliness—a key driver of poor health. A recent study by Fountain House found that 73% of new members reported loneliness at intake, far above the national average. Building more clubhouses can help close this gap and foster recovery through community.

Don’t ban the technology, but make it work better: Technology often exacerbates loneliness, but it can also be part of the solution. Young adults spend an average of 7–9 hours a day on screens, and heavy users report feeling lonelier than their peers, according to a 2022 Journal of Adolescence study. Instead of promoting endless passive scrolling, tech companies and schools should incentivize active digital engagement. For example, video chats are much better than likes (and even most parent psychologists agree that FaceTiming a parent or friend is OK screen time). Tech isn’t inherently alienating, but without redesign, it risks deepening the very isolation it's poised to help heal.

Reframe the conversation: Loneliness is a challenge in America, but I worry that we’re losing track of the real conversation. We need to include women and girls in the loneliness conversation, and we also need to realize that there is little casual evidence at this point showing that the reason men are acting the way they are is because of loneliness. Men may be 4 times more likely to die by suicide than their female peers, but guns are used in half of all suicides. Would this ratio still be the same if guns were so easily accessible? We also need to limit the domination of the manosphere to silence other epidemics that are challenging opportunities for women and have been going on for much longer (and that are more deadly).

My own personal opinion — male loneliness is an issue, but it isn’t the main issue. The US has deeper issues with guns, with schools, and with mental health support. The narrative of boys spending too much time online or playing too many video games is too convenient, too simple, to really address the underlying problems. The top map focused on loneliness in general because girls are struggling too, and have been for decades. We need to protect our children, but not at the cost of some over others.

If you’re down here, you should be subscribed. But if not, sign up for the American Inequality newsletter.

INTERESTING ON THE WEB

🩻 New resource from the Yale School of Public Health highlights emerging and ongoing health issues in different communities. Great maps - LINK

💧Meta built a new data center next door. Then the neighbor’s water taps went dry - LINK

🧑🏻🍼“Fathers approach parental leave very differently than mothers. Fathers are much more likely to take their paternity leave: during summer holidays; when their children are already in formal care; when mothers are likely around" - LINK (thank you to Robert Dur for highlighting)

💰 Every baby born between now and 2028 will get $1,000 from the government. Here is why that won’t make a dent in inequality - LINK

Another great post. Reminds me of the discussion in the book "Of Boys and Men". These sentences caught my attention in your post. "Geographically, the loneliness crisis is most acute in states with high unemployment, low levels of civic infrastructure, and limited access to mental health care."

It’s interesting to see that loneliness, regardless of gender, affects the non-college educated the most, while the college educated seem to report lower rates of loneliness.

It seems like being tied to institutions you care about, or ones that force you interact with other people are really the only antidote to loneliness. You see this in the fact that ironically, the more educated you are, the more likely you are to have frequent church attendance.

Anyone have any other theories on this?

As for gender, it’s also important to note the loneliness flips in old age with older women reporting more loneliness than old men.

This could be really concerning in the future with declining birth rates as in a country like Japan, the elderly loneliness rates are so severe that it’s become more common for elderly women to commit suicide. There are even these whole squads in Tokyo sent out to apartments, looking for elderly who have died alone without anyone knowing. It’s really sad and I’m concerned this tragic fate is coming to Americans since there’s no evidence that loneliness is gonna decrease and we’re having similar issues as Japan does with our birth rates. All of which could be exacerbated by the rise of AI…