Why U.S. Maternal Mortality is Better Than You Think (Pt. 1)

New research shows we may be drastically overcounting maternal mortality

This article is part 1 in a 2 part series on maternal mortality and inequality in America.

Send this email to a friend and join +16,000 subscribers for the American Inequality newsletter. Stay up to date on the biggest social issues of our time.

INTERESTING ON THE WEB

Tracking all of the government data websites that have been shut down (as I reported on a few weeks ago) - The Upshot

New paper in Nature using human mobility data to quantify experienced urban inequalities - Nature

Massive new WHO report on how to use data on health equity to improve outcomes for at-risk communities - World Health Organization

Does Elon Musk give to charities? Where is the Musk hospital? Where is the Musk library? - Bloomberg

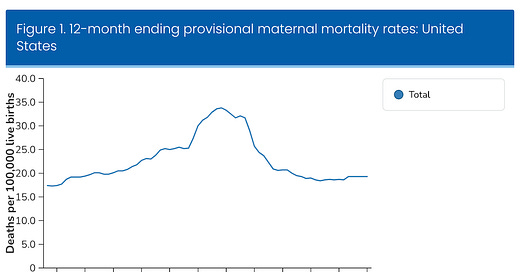

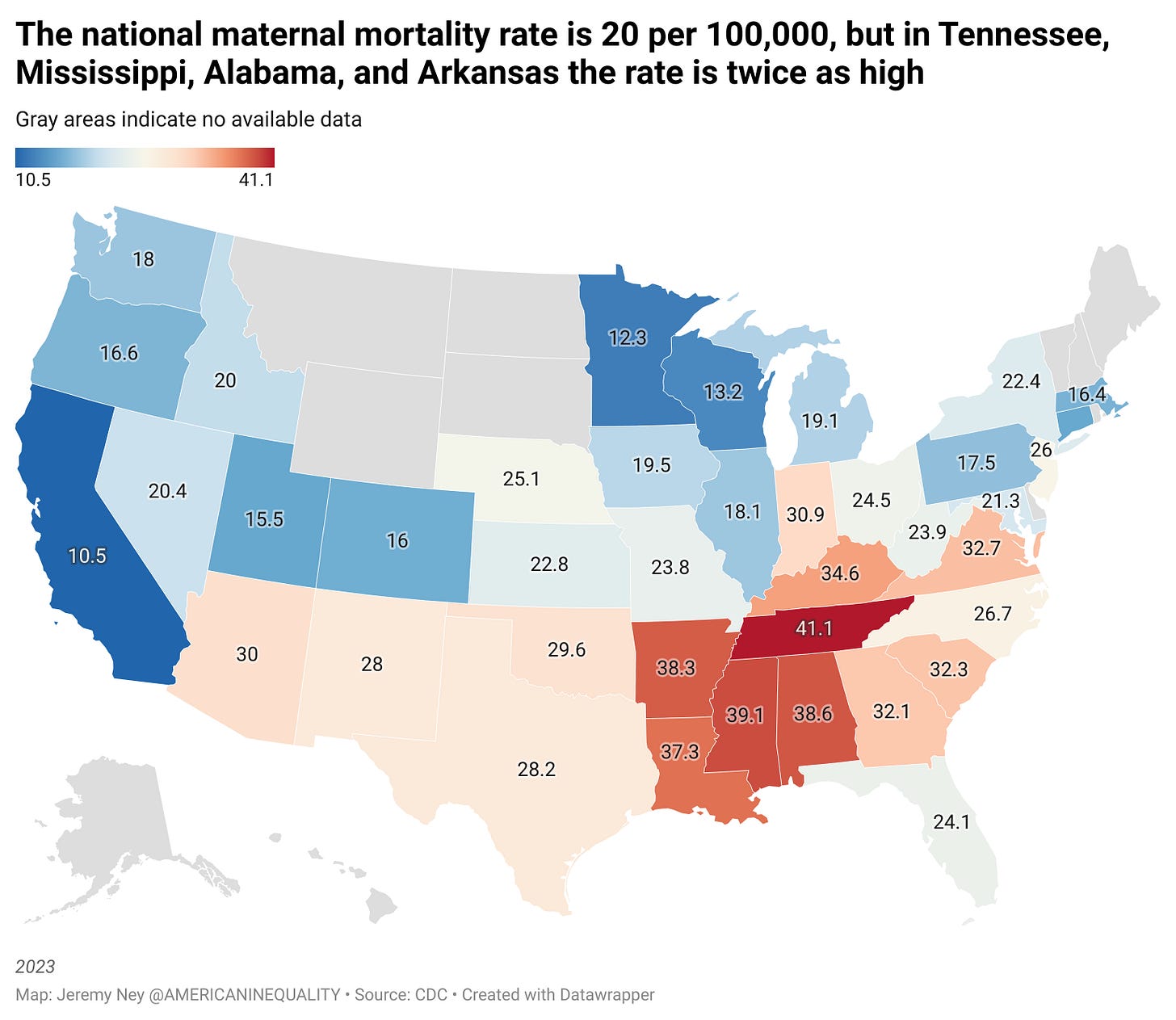

The current maternal mortality rate in America is 20 deaths per every 100,000 births, putting the US in a group alongside Iran and Lebanon, far out of reach of any of our peers. During the pandemic, the figures soared to 32.9 deaths for every 100,000 live births. The maternal mortality rate is shocking, but some interesting new research shows that this number doesn’t show the whole picture. Are that many women really dying in hospital beds while giving birth?

It turns out that homicide is the leading cause of death during pregnancy and the postpartum period in the United States. However, homicide and other violent causes are, by definition, not counted in estimates of maternal mortality, which fails to capture the totality of preventable death occurring among girls and women who are pregnant or in the postpartum period. This is what part 2 of this series will be about.

To understand why this data is so flawed, it's important to understand what the maternal mortality numbers represent, how those numbers are captured, and where public health officials decide what is included and excluded in these figures.

The CDC botched the rollout of maternal mortality

The CDC categorizes maternal death as a (a) death while a woman is in the hospital about to deliver; (b) a death while giving birth; or (c) a death 42 days or 6 weeks after birth. But only recently did the US begin systematically tracking this data.

In 1999, the CDC added a new checkbox on death certificates to begin tracking maternal mortality. The agency put the burden on the states to identify whether one of the 3 conditions above were met. States were then responsible for reporting that number to the central federal agency.

However, the rollout of the new maternal mortality checkbox was a disaster. Doctors weren’t properly trained on whether the pregnancy was the cause of death and states were allowed to adopt the checkbox on their own timeframes. If a woman dies in a car accident within 6 weeks after giving birth, is that a maternal mortality? What if she is pregnant and has a heart attack? On top of states having their own timelines, many of them also used different language on the death certificate questionnaires to understand if the death was related to the pregnancy or incidental.

For example, a doctor in one state might see: "Was the decedent pregnant at the time of death?" (Yes/No/Unknown)

While another doctor in a neighboring state would see: "Was the decedent pregnant or recently pregnant (within 42 days of death)?"

Whereas a third doctor might see: "Was the death pregnancy-related?"

Any time a state added the checkbox, the state maternal mortality rate suddenly doubled.This wasn’t necessarily because more women were dying from pregnancy, it was because the state finally decided to systematically ask the question.

Estimates of maternal death rates began to rise in 2003 when a pregnancy checkbox first appeared on U.S. death certificates. However, the CDC acknowledged that the governance around this data and the usage of that checkbox was faulty. 4 states had adopted it in 2003 and 18 had adopted it by 2007. The data flowing in was not even handed and it was still missing results from 32 other states.

Because of this data quality issue, the CDC stopped reporting the maternal mortality data for a full decade between 2007 and 2017.

By 2017 every state had adopted the approach. The CDC then spent huge resources training doctors, aligning the language on death certificates, and making sure that states were reporting in line with each other. In 2018, the agency acknowledged that it was likely still overcounting the data, but that things were on a much better track.

Is the new data correct? Unlikely

Why did the CDC say that it was overcounting the data and not undercounting it? What led them to this belief? A team of researchers took up this question and published their results in The American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

Rather than strictly relying on the checkbox and whether the woman was pregnant, these researchers used computer learning models to read the causes of death on the death certificate.

“If you’re pregnant and die in a car crash, that’s not a maternal death,” Cande Ananth said, one of the lead researchers on the groundbreaking report that shook the medical world. “A big change driving recent increases in the official numbers stems from the tendency to include more and more cancers unrelated to pregnancy in maternal death rates. A woman who had a diagnosis of breast cancer before conception and then died after the pregnancy ended or – a woman who would have died if she’d never gotten pregnant – will be counted as a maternal death.”

Ananth and K.S. Joseph, the other lead researcher, found that the maternal mortality rate in America is actually 10.4 per every 100,000 births, half of what the CDC’s official estimate says. This would put America much more in line with other wealthy nations like Canada, the UK, and France. Ananth’s team also showed that maternal mortality has remained relatively flat since 2002.

The CDC’s estimates on the other hand showed that maternal mortality rates had spiked to 34 deaths per 100,000 births in February 2022. This huge flux doesn’t show up in the new data.

Ananth’s data showed that the CDC was including more deaths as ‘maternal’ deaths than should be. Going beyond a simple box and using the text of what doctors used helped clear up the picture and show that the US was much better off for maternal mortality deaths.

However, Ananth’s team overlooked the single biggest cause of maternal mortality in America: homicides. Once we include this data into the picture, the rates tick back up again. This is what part 2 of this series will be about.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to American Inequality to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.