Violent Crime and Inequality

The most dangerous county borders the least dangerous county - what's the big difference?

St. Louis has the highest violent crime rate in America. 1 in every 50 people will experience violent crime there at some point in their lives. However, just on the other side of the Mississippi river and across the state line, Monroe County, Illinois has the lowest violent crime rate in America when looking at counties with populations above 10,000 people. Although these two counties border each other, what happened to create such starkly different outcomes?

Fear is the word that Tajaé Redden, 13, uses to describe her walk home from school in St. Louis after the bus drops her off. She knows that Missouri’s open-carry laws mean that “people sometimes turn to guns when they’re having a bad day.” Her mother waits at the bus stop every day for the children to get home, hoping they made it back safely that day. Jurnee Thompson, one of their neighbors, wasn’t so lucky and was killed in a parking lot on his way home from school. Jurnee was just 8 years old.

Violent crime in America has been decreasing for years, though some communities still see much higher rates.

This is because several studies from across the world have shown that places with higher inequality are more likely to have high rates of violent crime. The World Economic Forum explains:

Where a person is born and lives correlates with their overall life chances. Unsurprisingly, people living in environments characterized by high levels of economic and social inequality tend to be more exposed to violence and victimization than those living elsewhere. Neighborhoods exhibiting higher levels of income inequality and concentrated disadvantage experience higher levels of mistrust, social disorganization and violent crime. Failure to adequately address these issues dramatically reduces equality of opportunity and outcomes across generations, perpetuating violence.

Data from the FBI

Violent crime consists of 4 types of crime: murder, robbery, rape, and aggravated assault. Since 1930, the FBI has worked with over 18,000 city, university and college, county, state, tribal and federal law enforcement agencies to gather standardized data called the Uniform Crime Report (UCR) to analyze criminal activity in America. This article draws on the dataset from the FBI’s UCR.

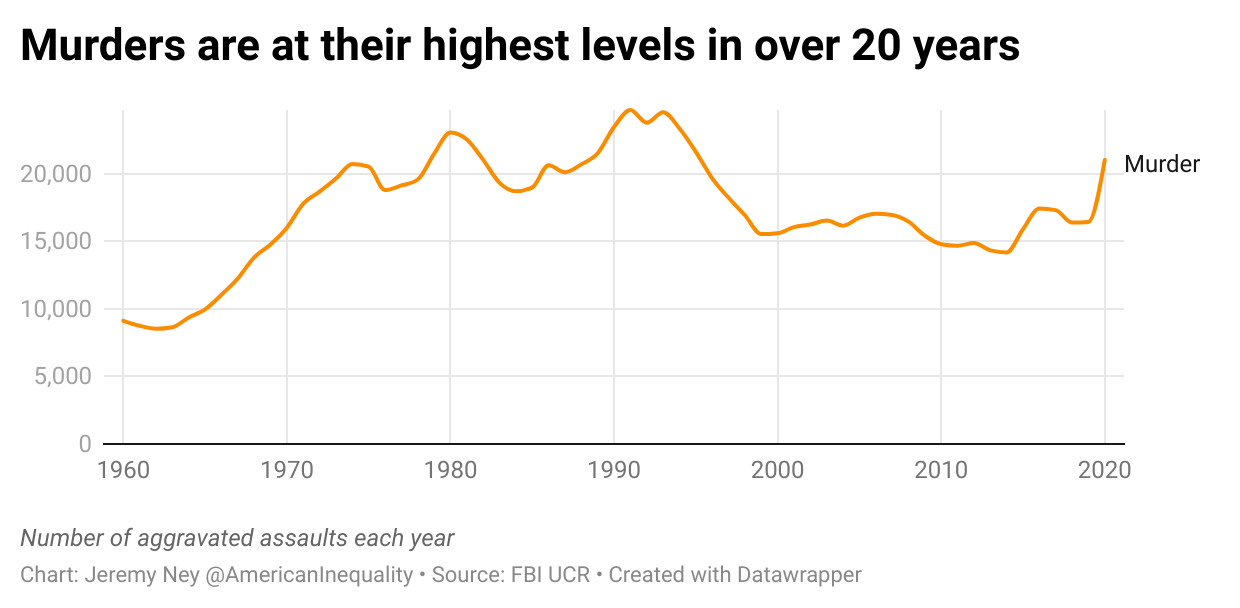

Murders are up 15%, reaching their highest levels in 20 years

While violent crimes overall are decreasing, murder rates have been increasing in recent years. Murders are up 15% in 2021 from the previous year, as the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated social, economic, and household challenges. Nevertheless, this phenomenon seems to be uniquely American, since other developed countries are not seeing nearly the same spike in murders that we have endured. While Canada and Mexico have seen some increase in murders, their increases are only in the single digits. Nearly all other OECD countries have seen declines.

According to a report from the National Conference for Community and Justice, homicides increased by 36% across 28 major U.S. cities — including Los Angeles, Atlanta, Detroit and Philadelphia — between June and October 2020, when compared to the same time period last year. One explanation is that these cities have also seen some of the highest rates of increasing unemployment in the past year as jobs have disappeared.

Black men are much more likely to be victims of homicides than any other group, but interestingly we see many more similarities across races when we control for income. Researchers looking at Columbus, Ohio found “violent crime rates for extremely disadvantaged white neighborhoods are more similar to rates for extremely disadvantaged black areas than to rates for other types of white neighborhoods.”

While assaults have not increased at nearly the same rates as murders, we do see a slow upward trend as well. Aggravated assaults have been decreasing since the early 1990s, but they began trending upwards in 2013. One explanation for this reversal is that as police protests spread in Obama’s last term and as rioters clashed in nearly every major city during Donald Trump’s presidency, assaults were repeatedly logged across America.

We believe there is lots of violent crime. The truth is, that’s not the case

Surveys show that people think that America is overrun with violent crime. 78% of Americans think there is more crime in America than there was a year ago and 38% think there is more crime in their local region. However, this couldn’t be further from the truth. Although murder and assault are up, violent crime overall is WAY down. The violent crime rate has fallen by half since 1993, from 750 crimes per 100,000 to 380 crimes per 100,000.

Americans are terrible at estimating crime rates. Survey respondents put their chance of being robbed in the coming year at 15%. Looking back, the actual rate of robbery was 1.2%.

Why do Americans think there is so much crime? The local news may be responsible. “If it bleeds, it leads” has long been an adage of the news industry. According to FiveThirtyEight, “Rarer crimes like murders received a lot more airtime than more common crimes like physical assault. And that hasn’t changed as the crime rate has fallen.”

We have failed to address root causes

On July 15, 2015 at the NAACP, Bill Clinton apologized for his 1994 Crime Bill. The former president explained, “I signed a bill that made the problem worse. And I want to admit that.” Sentencing for crimes drastically increased and America’s prison population exploded within a few short years. Crime rates fell not because we were helping combat inequalities and giving people more opportunity, more education, fairer housing, better healthcare, better paying jobs, and more access to social services like mental health support, addiction treatment, and rehabilitation.

The FBI’s data also shows that Black people make up 36% of those arrested for violent crimes, despite being only 13% of the population. Studies have also found that local news media disproportionately portray Black people as perpetrators of crime, and white people as victims. As the American legal system criminalizes Black people more, it continues to drive deeper wedges of inequality in our society.

Why is St. Louis so much more dangerous than Monroe?

Money is the answer. Income inequality is 45% higher in St. Louis than it is in Monroe County. The top 20% of earners in St. Louis make approximately $160,000 for every $10,000 that the bottom 20% of earners make while in Monroe the spread is much tighter. Additionally, people in Monroe just earn more money overall — median income in Monroe is 23% higher than in St. Louis, and 5x as many people live in poverty in St. Louis as compared to Monroe.

Policing practices contribute too. Monroe is one of only 7 counties in the state of Indiana that requires law enforcement to go through the rigorous SILEC program. While police training programs often have mixed results on their efficacy, the nonprofit Southwestern Illinois Law Enforcement Commission training program is designed “to encourage research and development directed toward new and improved methods for the prevention and reduction of crime.” This modern program trains officers in deescalation best-practices in high intensity scenarios, but also makes sure to recognize the local nature of its work. Interestingly enough, according to the local Illinois newspaper, Waterloo (which is the largest city in Monroe) has only 18 law enforcement employees for the city’s 10,000 person population whereas St. Louis has double this ratio with 38 law enforcement employees for every 10,000 residents.

Nevertheless, it is important to recognize that Monroe and St. Louis are drastically different on many structural levels. St. Louis has 30x the population, is 100 square miles larger, and has very segregated neighborhoods as a result of racial housing covenants and a history of redlining, still felt in the Delmar Divide.

The Path Forward

35 days into her role, Deputy Attorney General Lisa Monaco released a Comprehensive Strategy for Reducing Violent Crime memo that outlined 4 steps for combatting violence crime. The final sentence of the Department of Justice written preamble reads, “We know that violent crime is not a problem that can be solved by law enforcement alone.”

1) Build trust with communities

[Social] For the first time in 27 years, Gallup polls found that a majority of Americans do not trust law enforcement. Building trust isn’t easy, but holding officers accountable and engaging with communities through roundtables and town halls is a great place to start.

2) Invest in Early Community Based Interventions

[Community-Based] Beginning in 1991, researchers in Durham, Nashville, Seattle and rural Pennsylvania screened 10,000 5-year-old children for aggressive behavior problems, identifying those who were at highest risk of growing up to become violent adults. The researchers identified 900 children who were deemed at high risk, and of those, half were randomly assigned to a program called “Fast Track Intervention” aimed at early intervention community building. 19 years later in 2010, the authors found that Fast Track participants had drastically fewer convictions for violent and drug-related crimes, lower rates of serious substance abuse, lower rates of illegal sexual behavior, and fewer psychiatric problems than the control group. Early interventions administered by communities work, we just need to invest in them.

3) Focus on those who are actually violent

[Law Enforcement] Remember how Americans are really bad at estimating how much violent crime there is? Many law enforcement programs think they are reducing violent crime, but instead target spurious or uncorrelated traits. For example, a false belief was shared during the Trump presidency that illegal immigrants are a threat to public safety. However, this couldn’t be further from the truth. In fact, an analysis of Texas shows that illegal immigrants commit 56% fewer crimes than native-born Americans when accounting for population size. If we spent less money trying to build a wall and more money on violent crime reduction, we might be in better shape. In fact, the most serious urban violence is concentrated among less than 1% of a city’s population.

4) Measure the effectiveness of interventions

[Policy and Academia] The term “Evidenced Based Policing” has gained a lot of traction in recent years, but researchers and law enforcement need to have better agreement on the evidence that they are measuring. Project Exile, a 1990s program to deter gun violence, was hailed for its remarkable success. Congressman Bob Barr (GA-R) said in a Congressional hearing, “Project Exile illustrates that you don't need to be a rocket scientist to solve the problem of crime in our communities” and George W. Bush made it the cornerstone of his Project Safe Neighborhoods initiative that he put $2 billion of federal funding towards. As FiveThirtyEight explains though, “Soon after Exile went national, its record was called into question. Gun murder numbers rose every year but one through 2006. Two major research papers on the program’s effects in Richmond came to opposite conclusions.” We need to agree that we are measuring the reduction in murder, robbery, rape, and aggravated assault and not on tangential measurements of how long offenders are locked up or sentiments of safety.

In 1982, George L. Kelling and James Q. Wilson told a story about a window. Their article in the March issue of The Atlantic explained how one broken window leads to more broken windows, which signals the breakdown of neighborhood control, which signals that those neighborhoods are becoming “vulnerable to criminal invasion.” Kelling and Wilson argued that violence could be anywhere and we needed to crack down on crime. Not only do we now understand that broken-window policing is not effective, we also know that crime is not everywhere. Some communities struggle disproportionately compared to others. If we want to reduce violent crime and inequality, we must change the way that we protect those most in need.