Voter Turnout and Inequality

130 elections are being held across the US this week. Millions of Americans will not be eligible to participate.

Stacey Abrams was nominated for the 2021 Nobel Peace Prize because she got Americans to vote. Abrams helped turn Georgia Blue for the first time in nearly 30 years, brought more people to the ballot box than ever before in the state’s history, and even got record breaking turnout for the Senate runoff in January. While Abrams’ accomplishments are tremendous, her work highlights the huge inequalities that Americans face when it comes to voting. What if every state had a Stacey Abrams? What would it look like if every person took part in our country’s greatest display of democracy? What can we do to drive our country towards full civic engagement?

The 2020 election was hailed for its incredible voter turnout, but the national numbers obscure deep regional divides. Although 159 million people voted in the 2020 election, in many parts of America more than 70% of the voting age population did not go to the polls. When we peel back the layers and dive into the counties, we see that voting inequality persists.

Texas is the epicenter of voting inequality in America. Texas had 5 of the 10 worst counties for voter turnout in America. Reeves County in Texas, which had the worst turnout of any county in America. Of the region’s 11,000 eligible voters, 8,000 people did not vote. This means that only 30% of the county voted. Donald Trump won the county, which is 75% Latinx, by 900 votes.

Texas stands in stark contrast to Colorado, which has 6 of the 10 best counties for voter turnout. In Ouray County, CO which is the best county for voter turnout in America, only 10 people did not vote of the region’s 4,000 eligible voters. Biden won Ouray County, which is 93% white, by 800 votes.

What is driving this huge gap across regions?

Voter turnout has been plagued by a long history of racism, sexism, and fear-tactics in America. While the 15th Amendment gave Black people the right to vote in 1870, these rights were effectively nullified by a century of Jim Crow laws that instituted poll taxes, literacy tests, and intimidation efforts that kept millions of Black Americans from casting ballots. Again, the 19th Amendment gave women the right to vote in 1920, but these rights were not fully granted either since Black women, Native American women, and Asian women were excluded from voting for decades afterwards. And yet again, the Voting Rights Act in 1965 gave states more power to enforce the 15th and 19th Amendments, but recent Supreme Court cases like Shelby v. Holder (2013) have shown that the Act has not been living up to its goals.

Melissa Simmons is one of many Americans who is still a victim of this unjust system. Following a felony conviction, Melissa petitioned the governor of Virginia to restore her right to vote. Melissa then registered to vote, but when she showed up to her polling place on election day, she was told that she was not registered. She cast a provisional ballot, but recalls “It was a kick in the gut.”

Melissa is one of 5.2 million felons who are locked out of the American democratic process. In 11 states, people with felony convictions must receive a governor’s pardon, wait an extended amount of time, or complete some other action to restore their right to vote. The effect of felon disenfranchisement is felt acutely in Black communities, which face a disenfranchisement rate 3.7 times greater than majority-White communities.

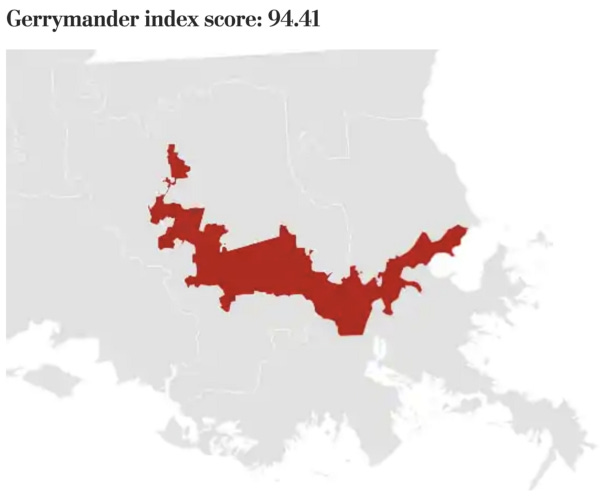

Gerrymandering has also effectively resulted in voter suppression in many areas. Gerrymandered districts emerge when policymakers redraw maps to include certain populations under one Representative, but this often diminishes the strength of a community’s voice. Gerrymandered regions may still have high voter turnout, but the data shows a high correlation between voter disenfranchisement and the most gerrymandered districts. Gerrymandering also creates strong psychological effects, since many people stay home when they think their vote won’t count.

Louisiana’s 2nd Congressional district and Texas’s 33rd Congressional district are two of the most gerrymandered in America. These Congressional districts effectively lump together liberal pockets (often African American) of the state into strangely drawn regions, which ends up creating highly-Democratic regions and loosely-Republican neighboring regions. Louisiana’s 2nd contains both New Orleans and Baton Rouge while Texas’s 33rd contains both Dallas and Forth Worth. North Carolina’s 12th district previously had the title of most gerrymandered district in the country, until Justice Elena Kagan at the Supreme Court finally ruled in 2017, after the case had gone to them twice before, that there was no compelling reason “for sorting voters based on race” and that the district had to be redrawn.

The Path Forward

The best solutions are sometimes the simplest — to reduce voting inequality, we must get more voters to vote. This consists of two parts — getting more voters registered and getting more valid votes from those voters.

The effort to achieve this, however, must be focused on the regions and communities most in need. Low voter turnout rates are concentrated among young people, low-income communities, and communities of color. In 2016, young people made up 33% of nonvoters, people of color made up 46% of nonvoters, and low-income people made up 56% of nonvoters. Accordingly, voter turnout efforts should be targeted at these groups and regions of the country with low voter turnout.

Register more voters at community organizations — While there are many political organizations dedicated to increasing civic engagement, nonprofit service providers should conduct civic outreach to reach a broader population. One study found that voters under 30 years old who were contacted by nonprofits turned out to vote at a rate 5.7% higher than uncontacted voters. Organizations like community health centers and food pantries are more likely to make contact and have built trust with groups who historically vote at lower rates. Hospitals in particular have been incredibly successful for voter registration. In 2020, healthcare providers helped 48,000 patients, clients or colleagues get ready to vote in over 700 hospitals, clinics, departments and medical programs across America. Vot-ER, a non-profit organization, provided tools for these healthcare providers to help their patients vote.

Get more valid votes through “No-Excuse” Absentee Voting —The COVID-19 pandemic showed the importance of absentee voting. Over 90 million absentee ballots were requested or sent to voters and states like Pennsylvania saw a +2,500% increase in absentee requests from the 2016 election. However, 23 states still require voters to provide an excuse why they need an absentee ballot and can’t vote in person. As of 2021, 11 states have proposed eliminating these excuse requirements, which would allow all voters to vote absentee, making the voting process more accessible for those who work hours or have unreliable access to transportation. No excuse absentee voting leads to a 3% increase in voter turnout over time, when controlling for other factors.

When it comes to combatting voter suppression, Biden has left much to be desired. Two bills in Congress - The For the People Act (HR1) and the reauthorization of the John Lewis Voting Rights Act - face an unpredictable future. 19 states have passed 33 laws that make it much harder for Americans to vote. Voting and inequality seems to be drastically on the rise. But voter suppression doesn’t always appear at the federal or state level - it occurs in neighborhoods and in polling stations and in apathy. We can all register neighbors to vote (18 states + DC have same-day registration), and with upcoming elections, it isn’t too late.

Special thanks to Rachel Breslau, a recent Tufts graduate and volunteer at Vot-ER, for her intrepid research, writing, and support