My hands-on experience gathering homelessness data in NYC

What I learned as a volunteer counting America’s homeless in Brooklyn, and how reliable that data is

I write a lot about data and what it tells us about the state of inequality in America. However, we only occasionally dig into how that data gets captured in the first place.

People tend to trust data. They believe that numbers are objective and that they tell us a quantitative story about the state of the world. But I had the experience of actually gathering those numbers this past January for homelessness in America. And what I found is that those numbers are not objective. The numbers are gathered by people like you and me and whether we are able to talk to a person on the street or not.

After I published my last newsletter on the historic rise in homelessness in America, I received a lot of questions about The Count. The Count is the preferred method in America for figuring out how many homeless people there are in this country: it involves thousands of volunteers combing the streets in every US city to count every homeless person in a specific and assigned geographic area.

I participated in New York City’s Count this year - what I found was a complex, fascinating, and at times confusing approach to identifying homeless individuals in the city that may be struggling most with this problem.

My takeaway: the US is dramatically undercounting the homeless population. When I was researching the last piece, I started to see this in stark relief - the NYC Department of Education estimates that there are 119,300 homeless students in the city; whereas HUD estimates that there are 103,200 homeless people in the entire state of New York. The math doesn’t add up.

Homelessness is having a meteoric rise

Homelessness in America increased 12% from last year, now reaching the highest point since 2007. At the same time, housing assistance has reached the lowest point in 25 years. 653,104 people were considered homeless in 2023, or roughly 1 in 5,000 Americans. Since the beginning of the pandemic, rents have increased 29.4% nationwide, which has contributed to the rise in homelessness.

Housing inventory has also hit a 20-year low, falling 14% in the past year alone.

Zig-zagging the streets from 10pm - 4am

The Count always occurs from 10pm to 4am in the last 10 days of January each year for each city in every state. The end of January is chosen because the colder weather pushes many homeless individuals into shelters, making them easier to count (plus volunteers walking the streets can help those who may be stuck outside on a cold night). This is known as a “Point-in-Time” count, or PIT.

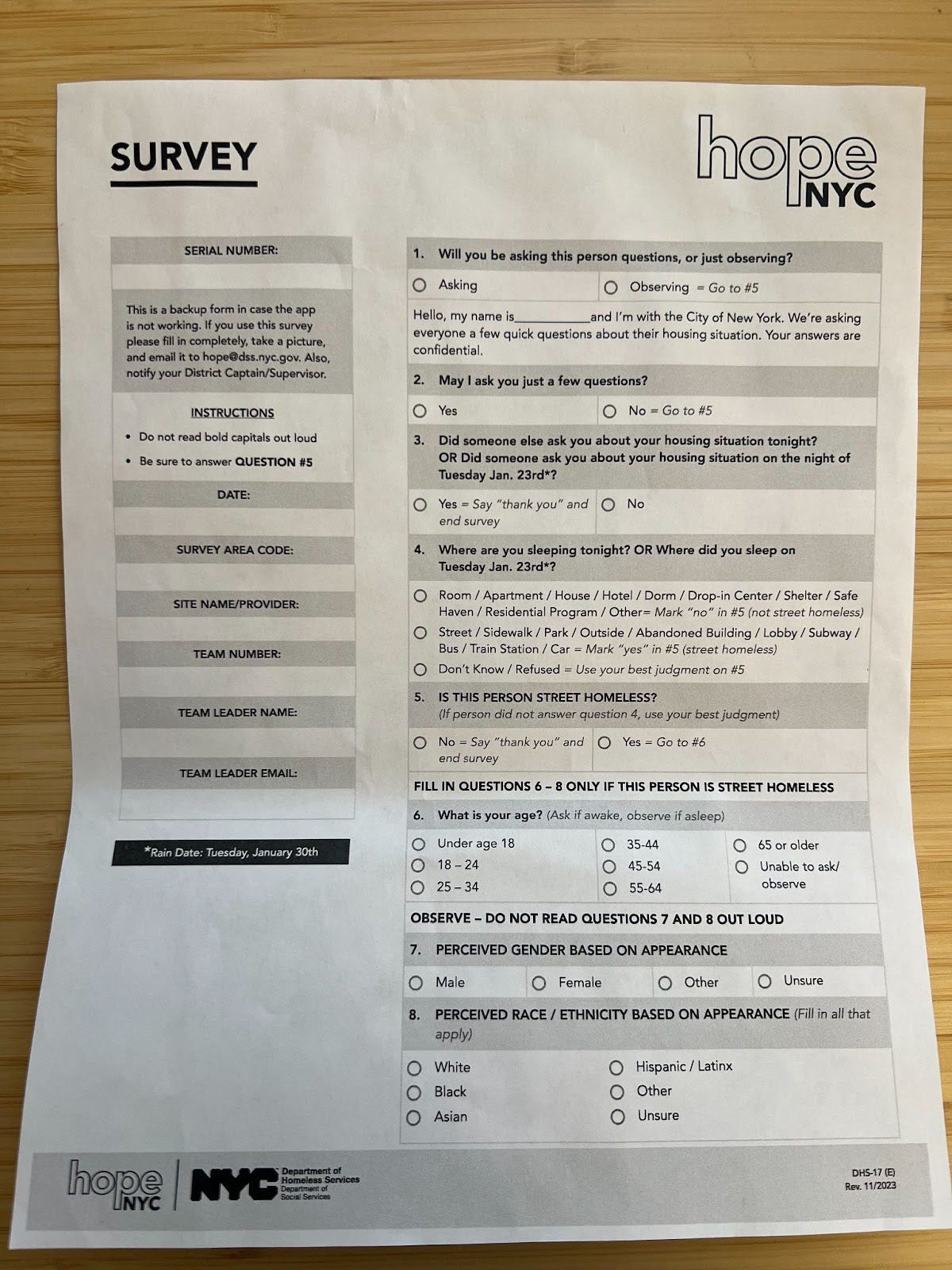

Each city’s homeless agency creates a mobile app or a paper questionnaire for volunteers to fill out. That city agency will then report the numbers to the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). In NYC, The Department of Homeless Services (DHS) leads the count each year. A 2021 report from the Government Accountability Office that reviewed the methodology in 41 states and found that while they all used in-person volunteers to conduct their counts, they used vastly different methodologies for calculating their homeless populations.

HUD has a mandate from Congress to conduct the Point-In-Time count. To achieve this, HUD provides funding to US cities to help enable the data collection. If cities do not conduct The Count, they lose funding from HUD.

The night of The Count and homelessness in NYC

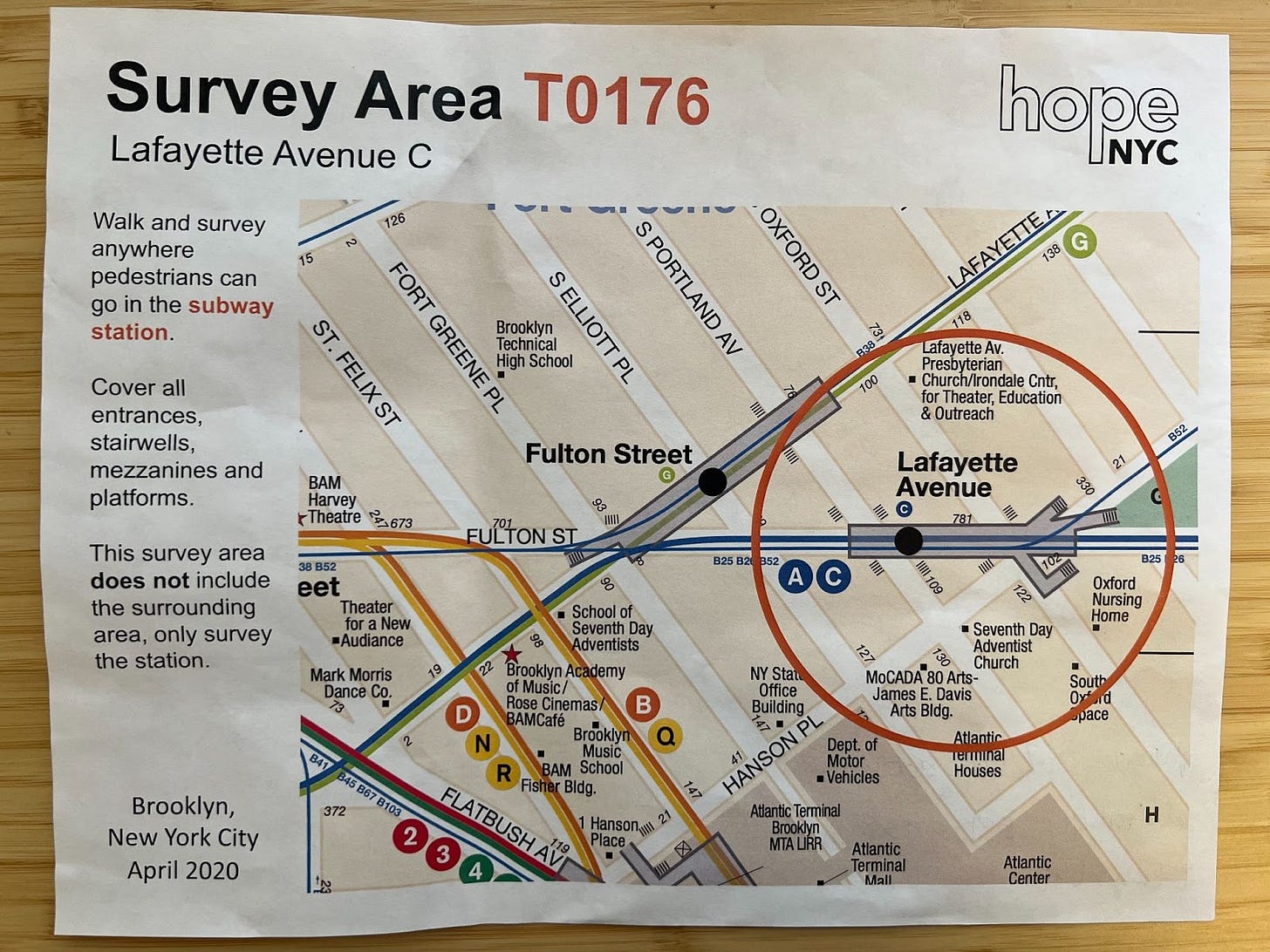

The Count was set for the night of January 23 and I received an email the day before asking me to watch a 35 minute training video. The email also told me to show up to P.S. 261 Zipporiah Mills School in warm clothing at 10pm to get ready to canvas the streets until 4am. My group was assigned 2 different areas and 1 subway station.

I tried to come in with an open mind about the efficacy of The Count’s methodology, and I was immediately pleasantly surprised that the approach used two key approaches to improve data collection: (1) counting everyone and (2) deploying decoys.

First, I had to interview every single person I saw and ask them about their housing situation. This meant talking to non-homeless people constantly - anyone on their walk home from dinner, talking with friends, it didn’t matter. This is designed to prevent bias in the survey of only reaching out to people who may look homeless. It also controls for volunteers having different perceptions about homeless populations. This was essential since the first person I engaged didn’t fit my perhaps problematic image of a homeless person; he was speaking on a cellphone, wearing pristine Nike shoes, and he informed me that he had been street homeless for the past 6 years.

Here is the survey I had to complete:

Second, the city puts “decoys” around various locations as a way to gauge The Count’s accuracy. In the NYC app I was using, I had 3 categories of people that I could register - homeless, housed, and decoy. I was told that if I encountered a decoy, they would give me a special code that I would put in the app to register them in this different section. Decoys are hugely important for data accuracy since it confirms that volunteers are in fact canvassing everyone that they see on the street. Without this control sample, data scientists wouldn’t be able to validate the accuracy of the canvassing.

In 2018, Javon Egyptt and Darryn Lubonski who had previously been homeless worked as decoys for the city’s count. After spending several hours in training with Silberman School of Social Work at Hunter College (which has a $133,000 contract with the city to train decoys), Javon and Darryn bundled up and waited for volunteer counters to find them. On average, about 90% of decoys are found, and most are found within two hours.

But even with these two tools to help validate data collection, I still found many issues with the methodology.

Random luck: At the end of the night, I noticed that the man whom I had spoken to at length was now in a new spot across the street. However, this was technically outside of our mandated zone, which means that if I hadn’t caught up with him earlier, I wouldn’t have been able to meet up with him then. With no other group in sight, this man may have evaded The Count simply by walking around and the random luck of the route we, or another group, happened to pick.

Picking and choosing data: When we entered the subway, we were not allowed to enter into subway cars. Although the C train pulled up while we were there and I could see people asleep in the cars loaded up with garbage bags in shopping carts, I wasn’t allowed to engage them or count them in my survey results. Only platforms, stairwells, and entrances were in bounds for our count. On cold nights it’s very common to see homeless people asleep in warmer subway cars. I’m still unsure how the city counts these individuals, but it felt like as volunteers we were told which data the city wanted to select.

Learning from NYC’s homeless

Early in the night, I had a long conversation with a homeless man that touched on many of the major issues both with The Count and homelessness in America.

The conversation started like all my conversations that nights with the first required question, “Hello, my name is Jeremy Ney and I’m with the City of New York. We’re asking everyone a few quick questions about their housing situation. Your answers are confidential. May I ask you just a few questions?” The next question asks if they’ve already been contacted by a volunteer that night.

He responded incredulously by asking what his incentives were to answer any of my questions. Many of the people we spoke with wanted to understand if they would be paid for filling out the questionnaire or how their personal information would be used. NYC does not offer funds to volunteers or to the homeless for participating in The Count.

The man also asked me why I was the one who was asking the questions and why he was living on the streets. Where was the justice in that? Why was I lucky enough to be holding an iPhone with a survey open while he was freezing on the streets outside of Atlantic Terminal in Brooklyn? I had no good response frankly, except for the painful luck of circumstance.

Finally, he wanted to understand how the data was going to be used. I explained that it helped NYC get the right resources into the right communities by knowing how large or small an issue might be. He wasn’t buying it and felt that NYC had continuously failed to give him the care he needed as an elderly Black man with a severe foot injury.

I did explain that we would be able to offer him help getting into a shelter that night. All volunteers were given a special number they could call and a van would arrive at that spot to take the person to a nearby shelter. Only one person we spoke with asked for this, but he left before the van arrived because he had to meet up with his girlfriend.

Bad data leads to bad resourcing

Although the volunteers were told that we could help any homeless person find a bed in a shelter that night, I did not know how that could be possible. NYC has a unique “right to shelter” law requires that the city to offer a safe bed for any person who asks for it. This law emerged in 1981, after a 26-year old lawyer named Robert Hayes filed a class-action lawsuit against the city and state of New York on behalf of homeless people facing overcrowding in shelters.

But the city does not know how many beds it actually needs because it does not have good data on homelessness in the city.

On any given night in NYC 850 people are waiting for a shelter bed and the average wait time to get a bed is nearly nine days. For migrants, the number is far higher. Moises Chacon’s number on the waitlist is 14,861; Jon Cordero’s number on the waitlist is in the 15,000s; and Oumar Camara’s number is 16,700 on the waitlist. All of these men have come up against NYC’s new 30-day limit on stays for single adults at any one homeless shelter.

If The Count were able to provide the city with the right numbers homeless people, then perhaps NYC would be able to provide the right number of beds and reduce wait times for the homeless population.

The Path Forward

A 2020 report from the Government Accountability Office agreed that The Count was not satisfactory for providing accurate information. The GAO “found HUD’s count likely underestimated the homeless population. Organizations across the U.S. provide data for this inherently difficult count. HUD could improve its instructions to them, which in turn could improve data quality.” Several solutions can improve the accuracy of our data collection, thereby improving our ability to give support to the most at-risk homeless communities.

Bring the homeless into shelters in the weeks prior - The zigzagging route of a street count is prone to errors and haphazard counting. However, if cities can encourage homeless individuals to come to shelters for a given night, either with food, blankets, clothing, wifi, or other resources and incentives, this will consolidate collection points. The Point-in-Time unsheltered count captures 37% of the homeless population on average in any given city, while the sheltered count captures the remaining 63%. Even if these numbers are not wholly accurate, creating more centralized locations for counting will improve accuracy.

Report on sampling bias - HUD does not require cities to report on their sampling methodologies or the possible error estimates of that sampling. GAO found that HUD does not report this because officials “believe sampling error is a difficult concept to convey to the public, and some [cities] may lack the technical expertise to develop measures of error.” However, without more detail on the calculations and what the standard error may be, it remains difficult to evaluate such statements.

Improved and scalable training for volunteers - Most volunteers that I worked with on the night of The Count did not know there was a training video. For the first 2 hours after arriving, we largely sat around and got to know each other. We had instructions read to us at around midnight, but many people remained confused about what they were supposed to do. This lack of training was most evident when the volunteers encountered individuals who really needed support, or when individuals started asking us questions like “who are you with?” and “which shelter are you sending me to?”

After Los Angeles counted zero homeless people in Venice in 2022, residents and officials protested the inaccurate count. LA then adopted many of the proposals outlined above - welcoming more homeless into shelters; hiring data scientists to improve the statistical methodology; and creating a more robust app to support volunteers. However, one of my close friends, Aaron Dannenbaum, participated in The Count in LA and had this to say:

“In the Palms neighborhood where I volunteered almost all of the counters were traveling in vehicles, which made it impossible to talk to individuals to confirm whether or not they were in fact homeless. As a result, counters were forced to make educated guesses as to whether a person looked homeless, which introduces a great deal of bias.

At least in cities that are more walkable than LA (and smaller geographically), volunteers have the ability to more deeply canvas the streets for individuals.

New York City and Los Angeles have the largest homeless populations in the country, accounting for nearly 20% of the national total. These two cities in particular would benefit from adopting the Path Forward solutions that may ensure that we can gather better data and in turn improve our resourcing for America’s homeless population.

This is excellent content. Thank you for sharing!

Thanks for breaking all of this down. I'd heard of the count before, but never looked into the process.