Literacy and Inequality

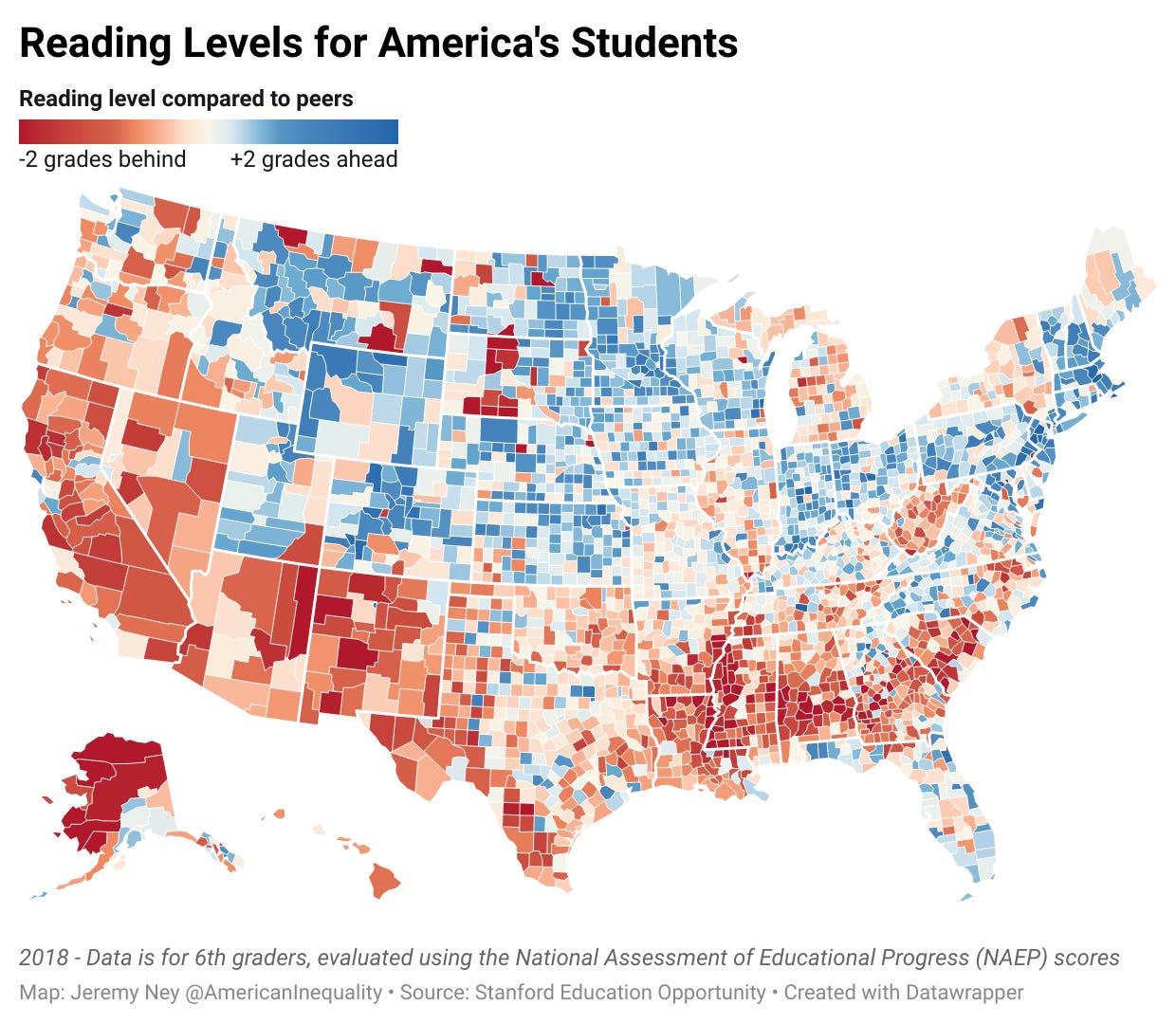

For our 10th article (!!!), we look at why 6th graders in the richest counties read 4 grade levels ahead of their peers in the poorest counties

Repeat after me: “Reading is hard.”

Repeat after me: “Reading is hard if you grow up in a poor county.”

Repeat after me: “Reading is hard if you grow up in a poor county and you are Black.”

Repeat after me: “Reading in America is unequal.”

Half of all US adults cannot read a book written at an 8th grade reading level. 20% of adults cannot read their local newspaper, and the Department of Education estimates that 36 million adults lack the basic reading proficiency to sustain employment.

When Americans can’t read, they die earlier, spend thousands more on healthcare, are more likely to have workplace accidents, are 2–4x more likely to be unemployed, and tend to have a worse understanding of their finances.

Instead, Americans who can read proficiently by the end of third grade are more likely to graduate from high school, are less likely to fall into poverty and are more likely to find a job that can adequately support their families. Data from over 200 million standardized reading scores given to 6th graders in every school district in America sheds light on reading and inequality in the United States.

Why can’t millions of Americans read?

First, learning is expensive. 61% of low-income families have no children’s books in their homes, which affects their kids’ ability to develop the skills to begin reading on their own. The Annie E. Casey Foundation reports that 66% of 4th graders read at a below proficient level, and of those, 82% are from low-income homes.

Second, intergenerational illiteracy makes it harder to break the cycle. 72% of children whose parents have low literacy skills will be at the lowest reading levels themselves. The home learning environment is a huge predictor of a child’s educational success — whether parents read to their children at night, whether they encourage reading for their kids, whether they help out with homework — and without that support at home, students struggle to read in the classroom. On top of this, dyslexia is hereditary and can be passed on to children.

Peggy Fleming, a mother of 2 in Kentucky, knows the challenge of intergenerational illiteracy. She never learned to read in school growing up, and when her children would come to her with questions about their reading assignments, she was unable to help them and they started doing worse in school. Peggy took it upon herself to take lessons to learn to read again, but millions aren’t so lucky to have a mom with the time, resources, or grit.

Students in Oglala Lakota County, South Dakota have the worst reading levels in the entire country. Compared to their peers, 6th graders in Oglala Lakota read 4.2 grade levels below what we would expect — in other words, they read as though they are 2nd graders. Readers may remember our profile on Oglala Lakota from the very first American Inequality article on life expectancy, since residents here also have the lowest life expectancy in the entire country.

Reading between the lines: Black and White, rich and poor

Students in rich counties greatly outperform their peers in poorer counties. Even if we hold all things equal — household composition, race, distance to school, etc — we still see that richer students do better than poorer students, often by as much as 4 grade levels. This means that a 6th grader in a county with a median income of $110,000 will be reading at an 8th grade level while a 6th grade in a county with a median income of $40,000 will be reading at a 4th grade level.

Huge reading gaps persist between Black students and White students. DC Public Schools have some of the worst racial reading gaps in the country. White students in DC Public Schools perform at 2.7 grade levels above their peers (i.e. White 6th graders score as though they are reading at nearly a 9th grade level) while Black students in DC Public Schools perform at 2.2 grade levels behind their peers (i.e. Black 6th graders score as though they are reading at below a 4th grade level). Students in the exact same classrooms are operating as though there is a 5-year gap between them.

Even controlling for income, the racial reading gap persists. In William S Hart Union County School District in LA, White families and Black families have exactly the same income, but White students perform 1 grade level above their peers while Black students perform 0.6 grade levels behind their peers.

Why do racial reading gaps persist?

This is a remarkably difficult question to answer, but a few possible reasons emerge.

First, Black 3rd graders are half as likely to be place in “gifted” programs as White 3rd graders. This means that from an early age these students are put in less rigorous courses and are thus ignored in schools. Jane Elliot’s research further supports this point, showing us what happens when we tell students they are not smart.

Second, majority White school districts receive $23 billion more in funding than majority Black school districts (or $2,556 per student in each school). Fewer books, fewer resources, and lower teacher pay mean that students in these regions suffer.

Third, and perhaps most importantly, school segregation means that students both within and across school districts learn at different rates and have vastly different educational experiences. Stanford Professor Sean Reardon, a leading expert in education and segregation sums it up:

“It’s the measure of segregation that is most strongly correlated to the racial achievement gap. The difference in the rate at which black, Hispanic, and white students go to school with poor classmates is the best predictor of the racial-achievement gap.”

The Path Forward

Educators, administrators, and policymakers have struggled for centuries to figure out the right tangible tactics for improving education. Do we bus students to better schools? Do we give families housing vouchers to move to better neighborhoods? Do we incentivize teachers to teach at struggling schools? The solutions below focus on reading specifically, as well as some new proposals that have gotten strong traction recently:

Require Reading Licenses for Teachers — Only 19 states require that teachers have sufficiently rigorous training for teaching students how to read. In these states, teachers have to pass a test indicating that they know how to actually teach students how to read. Meanwhile, 40% of teachers are relying on techniques to teach students how to read that will actually not work nor will it benefit the students. Texas recently passed bill HR3 in its state legislation to require all teachers to take the The Science of Teaching Reading (STR) Exam (293).

Case in point — In Union City, NJ, the school district’s superintendent, Silvia Abbato, uses federal funds to help pay for teachers to obtain graduate certifications as literacy specialists, and as a result, students consistently score a third-of-a-grade-above the national average on reading tests. This is exceptional because Union City has a median income of just $37,000 and only 18 percent of parents have a bachelor’s degree. About 95 percent of the students are Hispanic, and the vast majority of students qualify for free or reduced-price lunches.

Don’t Allow Parents and Teachers to Screen for Gifted Programs — While the No Child Left Behind Act provided a definition for what “gifted” means in a school context, most states rely on parents and teachers to identify these students. These tapped students then have to take a test, but these tests vary widely across states, and even within states. Ohio alone has 27 different tests for identifying gifted students. Instead of allowing parents to screen first, universal tests should be administered across districts or even states.

Case in point — Broward County in Florida administered a universal gifted test and found that the share of Latinx children identified as gifted tripled, to 6%t from 2%; the share of Black children rose to 3% from 1%; For Whites, the gain was more muted, to 8% from 6%. Unfortunately, Broward cut the program after the Great Recession due to budget constrains.

Deploy Controlled-Choice Integration in more districts — Controlled-Choice Integration is a strategy that has not only improved learning outcomes for 4 million students, but it has also saved costs for school districts across the country as well. With Controlled Choice Integration, parents effectively rank their top choice in schools, and the district reserves half of each school’s seats for low-income and half for higher-income students. Socioeconomic integration is a legal alternative to racial reintegration — ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in 2007 in the case of Parents Involved v. Seattle — and basically produces the same effects. This means that low-income students aren’t stuck in poorly funded schools, but also doesn’t require busing to send them to better regions.

Case in point — In 2009, President Obama introduced a new $120 million “Stronger Together” grant program to support local efforts to integrate schools by income. A RAND study found that this program helped low-income students in Montgomery County, Maryland boost their reading and math scores by 9 points, or almost 1 full-letter grade, moving from B students to A students. Programs have sprung up in both Red and Blue states — Cambridge, MA, and Berkeley, CA as well as Beaumont, TX; Nashville, TN; Omaha, NE; Rock Hill, SC; Salina, KS; and Troup County, GA.

Horace Mann should’ve met Phaedra Simon

“Education,” Horace Mann proclaimed in 1848, “is a great equalizer of the conditions of men, the balance wheel of the social machinery.” But poor funding, socioeconomic factors, and school segregation prevent Americans everywhere from learning and reading.

Phaedra Simon, a single mom of 3 from Opelousas, Louisiana quit her job so she could help teach her children to read. Median household income in Opelousas is $21,000, the city is 77% black, and students here on average read 1.3 grade levels below their peers. Phaedra realized that schools in the St. Landry Parish district weren’t doing enough for her kids. Even after sitting with them for hours each night and creating curricula, she explains “I’m not trained to teach them how to read. It’s totally different from how I learned.” She’s nervous that even with her extra help, they will still fall behind. Parents should not have to decide between keeping their jobs and whether their children are able to read.