Make sure to share this email with a friend or family member and tell them to subscribe to support this work!

Superfund sites are located in low-income neighborhoods and they have terrible health impacts on the children and families that live nearby. Among Black and Latinx communities, 1 in 4 people live within 3 miles of a Superfund site.

Living next to a Superfund site may stunt your academic performance, making it harder to achieve financial stability later in life. Children born within 2 miles of a Superfund site are 7.4% more likely to repeat a grade, have 0.6 standard deviation lower test scores, and are 6.6% more likely to be suspended from schools.

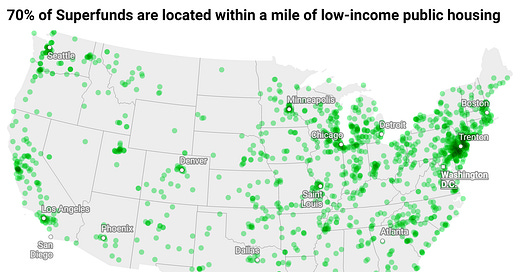

Superfunds are located next to low-income communities

1,318 of the nation’s 1,882 Superfund sites are located less than 1 mile from a public housing facility. In America’s public housing, 43% of tenants are Black on average, despite being only 14% of the population.

21 million Americans live next to Superfund sites and suffer from these effects. The Superfund list includes abandoned mines, radioactive landfills, shuttered military labs, closed factories, and other contaminated areas across nearly all 50 states.

Superfunds without enough funds

A Superfund is a toxic waste site that poses “a significant risk to human health or the environment.” Superfunds often consist of radioactive material, asbestos, lead, hazardous waste, oil leakage, or contaminated groundwater.

The name “Superfund” comes from a piece of 1980s legislation (CERCLA) that established a giant pot of money in the EPA (a $uper fund) to cleanup giant messes. This pot got much smaller in 1995 when an excise tax on large corporate polluters was not renewed, which slashed the funds available for cleaning up toxic sites. Fortunately, President Biden just renewed this tax in his newest infrastructure bill, which is expected to raise $14.5B over the next 10 years for cleanups. He also dedicated $1B to Superfund remediation.

Of more than 47,000 waste sites, the EPA has put +1,800 on the National Priorities List (NPL) since 1982. When polluters can’t be made to pay to cleanup the mess, the Superfund pays.

Superfunds have terrible impacts on health

Living next to a Superfund site leads to poor health outcomes. Many Americans who live near these toxic dumps develop cognitive challenges, die earlier, pay more in healthcare costs, and suffer from chemical exposure. As we’ve repeatedly seen in America, healthcare challenges are both social and economic challenges, and often prevent many from achieving the American Dream.

Cognitive development — Children born within 1 mile of a Superfund site are 10 percentage points more likely to be diagnosed with a cognitive disability. When families move away from superfund sites, the siblings in these families do not experience these challenges.

Life expectancy — Worse yet, living next to a superfund site decreases life expectancy by 15 months on average.

Pregnancy — Women living less than 1/4 of a mile away from a Superfund site during the first 3-months of their pregnancies are 2–4 times more likely to give birth to a child with a heart or neural tube defect.

Lead — Residents of the West Calumet Public Housing Complex in East Chicago felt the pains of living next to a Superfund site. After living in the housing complex for decades, residents learn that they had to relocate after the EPA found lead and arsenic the soil. The Anaconda Lead Products facility had been leaking these materials for decades. The EPA took soil samples in 2014 and 2015 and found that lead and arsenic levels were 200 times higher than the agency’s official safety level. 90% of the residents in Calumet are either Black or Latinx.

“We found out we were living on top of a lead refinery,” said Akeeshea Daniels, a former resident of the West Calumet Housing Complex. “By the time we learned that the soil under our homes was contaminated, 40% of the children tested in our community had elevated blood lead levels. There were over 680 children in our housing complex being poisoned by that lead every day.”

Superfund in focus: The Gowanus Canal

NY, NJ, and PA have a combined 300 Superfund sites, but perhaps none is more famous than New York’s own Gowanus Canal.

The Gowanus Canal was designated a Superfund site in 2010. Since 1880 when the Canal was first built, dozens of manufacturing plants, tanneries, and chemical plants operated along the Canal and discharged waste into it. The Canal festered for centuries as sewage and waste water continued to flow into it from around Brooklyn. In 1889, the city proposed spending $75K to clean up the canal (the equivalent of $2M today) but this was deemed too expensive at a time when the only people who lived nearby were blue-collar manufacturing workers. Now that the median income in Gowanus is $119K, the city has decided to spend $1.5B to clean up the site.

The Path Forward

3 solutions can help us combat Superfunds and inequality - We need to (1) add more toxic chemicals to the Substance Priority List on a more regular basis; (2) hold parties accountable when they pollute areas; and (3) better prioritize toxic site cleanup to focus more on equity instead of ease.

More regularly update the toxic chemicals list — The EPA’s Substance Priority List is updated every 2 years to determine which chemicals are dangerous enough to be cleaned up. This means that families can spend a dangerous amount of time living around toxic chemicals that just haven’t made it onto the list. 275 chemicals are currently on the Substance Priority List. The list should instead be updated annually so that Superfund sites do not get neglected and can be cleaned up with greater urgency. In the 8 years from 1992–2000, 153 chemicals were added to the list. In the 16 years from 2001–2017, only 51 chemicals were added.

Improve waste accountability—The EPA isn’t the only ones responsible for cleanups. “Potentially Responsible Parties” (PRPs) that dump toxic chemicals are the ones who are supposed to be principally responsible for cleaning up any mess. The law relies on 6 factors called “Gore Factors” to create a standard of proof, but these factors are not clear on what happens if multiple factories are polluting the same river, or about who is responsible if a large company acquires a smaller one that had been polluting for years. The Gore Factors ought to be revisited to improve how we evaluate PRPs.

Prioritize the most toxic sites for cleanup — The EPA can do more to support the most vulnerable communities instead of sites that are easiest to cleanup. The EPA currently uses a “Hazard Ranking System” to score Superfund sites along a scale of 1–100 to determine the cleanup prioritization of a site (the higher the score, the sooner it gets cleaned). This ranking does not account for the impact a Superfund site may have on a low-income population. Instead, the the ranking skews heavily towards ease of cleaning. Just because work is hard, doesn’t mean it can’t be prioritized. The EPA should add a new variable to score how much a project supports vulnerable communities.

Melissa Nootz was priced out of her home and forced to move into a more affordable house near a Superfund site in Anaconda, Montana. Melissa wanted to raise a family there, so during her pregnancy, her husband spent months shoveling toxic dirt out of their yard in wheelbarrows to get a swing-set ready for their baby. The government wasn’t coming quickly enough. After her first miscarriage, Melissa gave birth to a baby girl on Christmas Day. Miscarriages can be tied to living near heavy-metal exposure. But all that exposure left her daughter very ill. Melissa explains: “When she is 1, a routine test shows my baby girl has lead in her blood. My husband and I faithfully kept our vows, and we feel cheated and betrayed and utterly, helplessly devastated.”