Does Data Shape Our Identities?

The 2030 Census put out a call for help. The results may redefine how we view communities in America

Listen to the podcast version of this article recorded with NotebookLM. Share the newsletter with a friend.

A REQUEST: I’m looking to connect with people who have lived or worked in the Imperial Valley, California. If this is you or someone you know, please reply to this email or leave a comment!

Samera Hadi identifies as Yemeni American, but explains that “the categories of the Census don’t speak to my identity as Arab or, more specifically, Yemeni. I don’t walk through this world as a white person, I don’t get those privileges as a white person, I don’t have white culture.” For every Census , Samera would have been categorized as White. That might all change in 2030.

Samera wears a headscarf and is from San Jose, California. She recently moved to Chicago and began working with high school age refugee girls seeking educational and social support. She also has two daughters of her own and is trying to help them understand their identities as they grow up in a diverse city that welcomes them but in a country that doesn’t always recognize them in official measures and categories.

On November 18, the Census Bureau put out a call asking for help defining race and ethnicity. Bureau demographers started to work on the 2030 census and explained, “Public feedback on the code list is essential to making sure future data on race/ethnicity groups accurately reflect our nation’s diverse population.” The main request the Census made was for people to submit identity groups that might be missing from the code list.

At a time when ‘identity’ and identity politics are such fixtures of our national conversation and when the census is trying to understand what all the different identities might be, I thought I’d try to understand where some of this might be headed. The way we categorize identities might be driving our growing divides. Or it might be missing the picture altogether.

A long awaited new category

A new category is coming to the 2030 census that advocates have been championing for over three decades: Middle Eastern or North African (MENA). Matthew Stiffler, a University of Michigan lecturer on Arab American studies, explained, “The MENA community fought to be white in the early parts of the 1900s and they achieved that, but as politics and world affairs developed later that century and into the 2000s, it became clear that Arab and MENA folks were not going to be treated as white.” The Census estimates that more than 4 million people will select this category in the 2030 census.

Perhaps most importantly, the census is used as the #1 source for allocating funds both in the private and public sectors. Federal funding for many social services and apportioning House seats all comes from the Census. The budget documents for SNAP, Medicaid, Housing Choice Vouchers, and the main programs for childcare and job training rely on census data. Marketing, advertising, and eCommerce companies rely on census data to identify different populations in certain regions they are trying to serve.

Changing with the times

Identity categories are not immutable. The 1790 census had just 5 categories, with two of them including ‘slaves’ and ‘all other free persons’. Prior to 2000, the census did not permit people to list mixed or multiple racial identities.

The updates to the Census try to reflect the current identities of the nation, but those changes have created some unexpected pushback. Recent social-psychological research reveals that many whites react negatively to the idea of a majority-minority society and assert more conservative attitudes because of it. When white people realize that other racial groups are occupying a larger share of the population, this has a causal effect in making the white people more conservative.

We can’t change what we can’t measure

This past spring, I was speaking at Georgetown and a student raised his hand and asked something I had never heard, “Isn’t the chart only telling a narrow part of the story?” he asked. “Why are you not including other demographics like Asians or Native Americans?” I had pulled up one of my charts showing Black vs. White vs. Hispanic homeownership rates over the last 30 years. I had published this chart 2 years earlier and used it in dozens of presentations to show that Black home ownership rates are consistently half those of White homeownership.

The student was right in many ways, but my challenge was that I was just reflecting a perhaps bigger issue. The Federal Reserve has never published homeownership data on Native Americans and only in 2016 did it start publishing data on Asian homeownership, though this was lumped together with Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders. The only data going back to 1994 was for these 3 demographics of Black, White, and Hispanic.

We cannot change what we cannot see. When policymakers, economists, and politicians don’t know how bad an issue is for a certain population, they may never be able to enact meaningful change for that group. This is especially important now when every project needs to be able to prove its efficacy.

Who does the Census identify?

The code list has 7,054 terms that stretch across 8 main categories - White, Hispanic or Latino, Black or African American, Asian, American Indian or Alaska Native, Middle Eastern or North African, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander, or Some Other Race and/or ethnicity. Within these 8 main categories, there are many sub-sections that drive the distinctions.

Nationalities (e.g., Chinese, Argentinean).

Transnational groups (e.g., Roma, Hmong).

Ethno-religious responses (e.g., Sikh, Chaldean).

Subnational ethnic groups (e.g., Igbo, Sicilian).

Pan-ethnic terms (e.g., Arab, Latino).

Broad geographic terms (e.g., European, African).

Terms indicating Multiracial/Multiethnic responses (e.g., Mixed, Multiracial).

Federally and state-recognized tribes and villages, unrecognized tribes, and general terms for tribes in the United States (e.g., Navajo Nation, Cherokee).

Canadian First Nations and Central and South American Indian groups (e.g., Brokenhead Ojibway Nation, Maya).

These different categories also make a huge difference for how Americans see themselves. As 538 explains, “The first significant release of the 2020 census data arrived in August, and it paints a picture of America unlike any we have ever seen before. The share of Americans who identify as white fell 11 percentage points, from 72% to 62%, while the number of Americans who identify as multiracial more than tripled, from nearly 3% in 2010 to over 10% in 2020.” This was not due to massive shifts in demographics over the 10 year period.

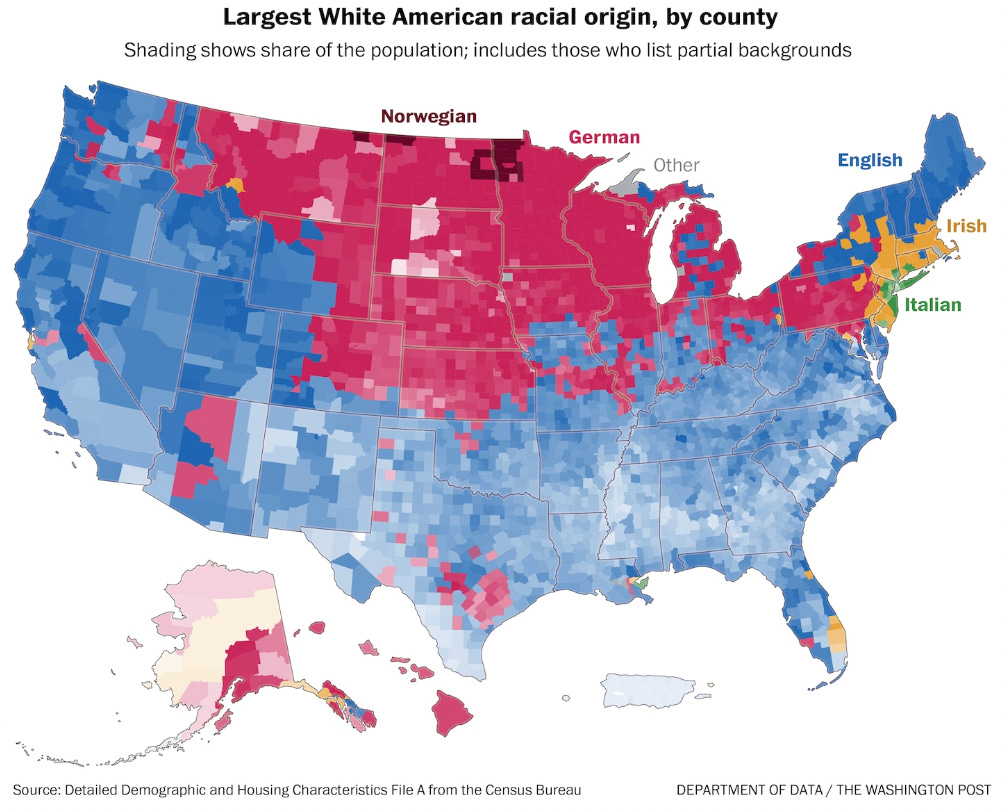

America’s largest ethnic group is German. Or maybe it is English. If you want to understand why we might not actually know, despite a change to the 2020, read this incredible act of journalism by our friend of American Inequality and data journalist Andrew Van Dam.

Gender identity and sexual orientation

The census is also evaluating whether to ask about sexual orientation and gender identity. Earlier in 2024, Census officials sent out hundreds of thousands of ballots and opened up a comment period as well to understand what language would be sufficient for asking this question and whether it brought back responses that could be useful. The trial questionnaire is testing “degenderizing” questions about relationships in a household by changing options like “biological son” or “biological daughter” to “biological child.” On the sexual orientation question, respondents can provide a write-in response if they don’t see themselves in the gay or lesbian, straight or bisexual options.

One way to view this is that politics drives data. Data is not ‘objective’ – we create the categories. We decide what to measure. In this case, one could argue that the questions are becoming less detailed (i.e. removing categories) in favor of a more gender neutral category that doesn’t label a child in a certain way.

The Path Forward

Data is never perfect. But the Census is such an important measure that we need to get it as right as we can. Here are a few things I realized along the way of writing this piece.

Improve multiracial categories: Most of the multiracial categories are large catch-alls right now. The different options are - Multicultural. Multiracial. Biracial. Some other race or ethnicity. In 1980, just 5% of US children had mixed parentage, compared with 16% four decades later. Much evidence suggests that racial diversity within family units will increase. These broad categories create both confusion and probably underrepresent the growth of multiracial communities in America.

Expand ethno-religious categories: Religious minorities need better protections and without proper identification of those groups it can be hard to fund those programs or clarify who we are talking about. The Census currently has categories of Copt/Coptic, Sikh, Hindu, Druze, and Yazidis to name a few. Advocates have long argued that Ashkenazi, Zoroastrians, or Igbo ought to be included. Most of these groups typically use the ‘ancestry’ category to delineate these, but write-ins often create data challenges.

Don’t do what the French did: In 1978, the French government banned censuses on race and ethnic origin. The law was passed because these types of lists were used during WW2 to round up French jews (though I couldn’t figure out why it took the French more than 30 years to pass the law then — definitely leave a comment or email back here if you know). The language of the law advocates making France a ‘color-blind’ country. French policymakers will instead focus on geographic regions to advance different socioeconomic goals, which can get close as we know #maps. The US has a very different history, one that involves slavery, internment camps, destruction of native lands, and ethnic quotas. Not looking at a problem doesn’t make it go away. The census should continue to expand its categories, not follow the French model that has made race a social taboo.

INTERESTING ON THE WEB

My life as a homeless man in America. Stories from Rhode Island - Esquire

Everybody loves FRED (Federal Reserve Economic Data). I can tell you that I too am in love and if you’re not yet, you should be - NYTimes

What makes the US truly unique, as shown in some great charts - FT

One organization distributed 5.3 billion meals to hungry Americans in 2023. Why can’t we feed people in the richest nation in the world? - NYTimes

We helped raise $560,000 dollars in our GiveDirectly campaign for families in Rwanda - Campaign

I enjoyed this essay immensely. The nuance and complexity of race today doesn't lend itself to black and white (no pun intended) bright line distinctions. Race is no longer a social construction (cue the one-drop rule). Instead and in the year 2024, there are innumerable variations of race and/or ethnicity. I have a distant cousin who I first thought was white. When I learned he was the descendant of free blacks in America, I perceived him as black. He eventually disabused me of my visceral desire to place a race/ethnic label on him. He self-identifies as a human being. How would the 2030 U.S. Census account for his human existence?

What does it mean to be recorded as "black" on the 2030 U.S. Census? Suppose one's great grandmother was born black in Louisiana but passed for white in New York State? Does the census permit this person to self-identify as white? Multi-racial? Black under the one-drop rule? I am zeroing in on self-identity of race and ethnicity, not social construction.

Here's another example -- me. When I was born, I was assigned the race "Colored" by the state of Virginia. I grew up in 92% to 95% white public suburban schools in the post-Jim Crow era. I have retired now from Blackness since I do not define black identity as dogma and slogan words. How should I self-identify on the 2030 U.S. Census and be authentic to my self identity? I have more in common with white suburban southerners and my genetic heritage is not mono racial. Would the 2030 Census allow me to check two or more races and/or multi-racial?

Suppose a young woman is half black and half white. She identifies as half white privileged and half black. Would the 2030 U.S. Census permit this woman to check the two races box? The multiracial box? Just questions I have for the essayist and commentators. Thanks for your words on a fascinating topic. We must accommodate the growing trend of fluid identity when it comes to race and ethnicity.

Whatever Blackness means today, it shares very little with the meaning and definition of Blackness in the 1790 U.S. Census. The trend of fluid identity will continue to accelerate in the 2030s and 2040s. Self-identity falls along a spectrum.

Seems like there's still just tremendous confusion between the concepts of "race" and "ethnicity". MENA being a subcategory of white, rather than it's own identity, is solidly rooted in the ideologies of racism that generated American Slavery, Jim Crow, etc, that required these umbrella racial categories to be cobbled together from ethnic groupings.

But yet we still think about white, asian or black as "racial categories", when in reality, at best they are groupings of many ethnicities, some of which fit relatively comfortably and reasonably into their census grouping (maybe for example, Black immigrants from Jamaica, or a White immigrant from the UK) but many of which don't.

MENA is under discussion because of that misfit, but others are very numerous. A short list off the top of my head includes: Mestizos from LatAm and Pardos from Brazil, Afghan refugees, immigrants from the Caucuses and much of Western Asian, Somalis and Ethiopians, the Amish, etc... The grouping of South Asian ancestry with East Asian is especially clumsy and looks increasingly silly as time goes by.

The social construct of race is never going to account for these diverse identities in a realistic way. And it's not needed to! If a person wants to, for example, account for harms done due to redlining or slavery, then what you want to know is if a person or their ancestors were harmed by those policies. If instead what you want to do is counter name-based resume discrimination, then people with distinctly "Black" names and people with Somali names need to be accounted for differently, based on the realities facing their ethnic groups, not based on their "race". If a researcher, journalist or intellectual wants to group Somalis and American Descendants of Slavery into one category for whatever their purpose it, they should be able to, but we don't need to force people into these categories right at the data collection stage.