Why does inequality matter?

As a new dad I've been thinking a lot about what a good world needs to look like

Listen to the podcast version of this article recorded with NotebookLM. Share the newsletter with a friend.

On December 4, 2013 President Barack Obama gave a speech in one of the poorest areas of the nation’s capital and declared that inequality was the defining issue of our time. I remember listening to the speech and being struck by the boldness of the claim. President Obama had taken on so many issues - climate change, which could wipe out humanity; the worst financial crisis in decades, which cost millions of Americans their homes and jobs; and the biggest overhaul to our healthcare system in years. Why was inequality the number one issue?

For this article, I’m going to do something a bit different: I’m going to write about why inequality matters. There is more to inequality than just a sense of right or wrong. For most of us, inequality just feels bad. But the truth is that inequality matters is far more important - impacting economic growth, how we shape policies, and the types of institutions we invest in.

The main takeaways:

Inequality is bad for upward mobility, making it harder for children to earn more than their parents

Inequality is bad for GDP growth for advanced economies like America’s

Concentrating resources results in “lost Einsteins”

Investing in low-income children is the best way to combat inequality

Thinking about the future

I recently became a new dad and so I’ve been thinking a lot about my son’s future and the world I want him to grow up in. At the same time, my wife and I are also meeting so many other new parents who too are navigating the challenges of raising kids well and trying to set them up for success. On top of this, as I’m sitting with my son I’m getting constant NYTimes push notifications about the election, wars abroad, and social issues that seem to be spiraling out of control. My own personal sense of why inequality matters isn’t just for the world I want for my own kid, but for all kids in the US who want to have a brighter future.

For me, I spend all of this time and effort writing these articles because it can make a difference. One father wrote me after I published the article on veterans and suicide saying that the military base that I highlighted in the article as having the worst suicide rate was where his son had died from suicide and he was grateful that more people were highlighting the issues. I’ve worked with nonprofits and legal advocacy groups that have used our maps to direct tens of thousands of grant dollars to struggling regions. The concepts from this newsletter are now taught in more than 30 schools across the US and have made their ways into dozens of government reports and conferences. After every article, I get dozens of responses directly emailed or in comments talking about how a person or their family member has struggled with the topic at hand and they are glad to finally see some data validating it.

One parent that I think a lot about when I’m writing is Akeesha Daniels. Daniels is a Black woman who lived in public housing in East Chicago but knew that something was wrong because her kids were always getting sick. She talked with her neighbors and found out that their kids were getting sick too. The families filed a petition with the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and realized that the water and yard where their kids would play was contaminated with lead. The housing project was built on top of an old lead refinery and the land was chosen because it was the cheapest available, despite the fact that city officials knew that a company had been leaching lead into the ground for decades. It is well known that children with lead poisoning perform consistently worse in schools, which haunts them for years leading to lower earnings later in life. “There were over 680 children in our housing complex being poisoned by lead every day,” said Daniels.

Daniels’s story epitomizes so many of the reasons why I care about inequality. If we don’t give people a fair shot, either because we gave them bad housing, bad water, bad land, bad quality of life, or bad health, it can create ripple effects through our communities for generations. Kids do worse in school, have worse jobs, and have fewer opportunities later in life. When I think about those 680 kids I can’t help but wonder what I would do if I found out that my son had been playing in those same yards and drinking that same water. But inequality is about more than just the golden rule, and because this is the American Inequality newsletter, I’m going to focus on the data-driven solutions.

What are we trying to accomplish?

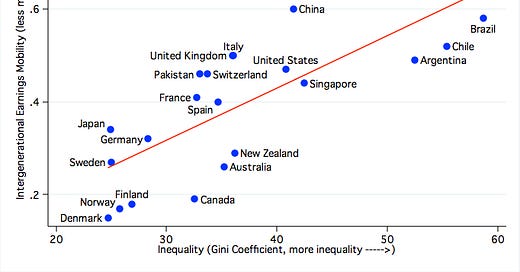

The number one reason why inequality is bad is that it reduces intergenerational mobility. This relationship, known as “The Great Gatsby Curve”, was made by famous by Miles Corak in 2013 and explains that the more inequality that a country has, the less likely it is that children will make more money than their parents did. This is one of the key parts of the American Dream, that each successive generation does a bit better than the last. With high levels of inequality, if your parents are in the 50th percentile (i.e. the middle class) it is more likely that you end up in the 30th percentile (i.e. low-income).

Corak explained that the trend of declining intergenerational mobility was getting worse for Americans. The data showed that the wealthiest Americans were pulling up the ladder behind them, making it far more difficult for others to make their way up the earnings rungs. Don’t you want your kid to have a better life than you?

Is some amount of inequality necessary?

One of the key questions about inequality, particularly in capitalist countries, is whether this is a natural byproduct of countries getting richer. Of course it would be harder for people to reach those levels of uber wealth for the top 0.1%, right? I’m generally wary of any economic argument that argues for a ‘natural’ order of things so here are the facts.

The answer about whether inequality can help your economy grow is that it actually depends on what type of economy you have. The research shows that there might be some level of inequality that can help for developing economies, but that high levels of inequality for advanced economies will reduce incomes on average. For a country like the US, researchers turn to the “Kuznets Curve” and see that higher levels of inequality reduce our income per capita. More inequality makes the US worse off.

Proponents who argue that inequality is necessary for an economy point to studies of innovation and invention. The argument goes that if we look at the history of patents in the US, we find that concentrating resources in certain areas (universities, San Francisco, Boston) results in more innovation and more patents coming from those areas. This by its nature increases inequality because we are not equally distributing resources. They argue we need to keep giving all our funds to Silicon Valley and Harvard and MIT because that is where the most important inventions are coming from.

The reason that this argument is faulty is that this is not causal. Raj Chetty, one of the youngest tenured faculty members at Harvard, often talks about “lost Einsteins” because of our failure to equally distribute resources across the US. Why would creativity be concentrated in some cities? Isn’t it just as likely that an Einstein is born in Cincinnati as San Francisco? Chetty grew up in New Delhi and saw how fortunate some were and others weren’t for no fault of their own.

Why aren’t we doing more to combat inequality?

How would you end inequality? Arthur Okun explains the concept of “the leaky bucket.” If you are trying to give money to poor people, and you had to put those resources into a bucket to send it over to them, how much money would you be willing to leak to get it to there? Would you be ok losing $500 for every $4,000 you gave? What about losing $3,000? Okun’s leaky bucket explains the administrative costs of providing welfare in America. Offering food stamps, housing vouchers, and tax credits require hundreds of thousands of personnel to administer. Advocates for universal basic income often talk about the leaky bucket because they say that it would be a cheap way (i.e. low leakiness since everyone gets it) to administer a way to reduce inequality.

Where would you start? Is the goal to reduce inequality for your country, your state, the world? $3,000 could save one person’s life in Nigeria by providing them with enough medical resources to avoid common lethal diseases like malaria. Do you weigh different people’s lives differently, perhaps depending on if they are old or young?

The World Health Organization uses an approach called DALYs (Disability Adjusted Life Years) where 1 DALY represents the loss of the equivalent of one year of full health. Some argue that every policy should maximize the total number of DALYs, essentially saying we should do everything we can to promote more years of healthy life.

But what about marginalized groups that might need special protections? Do you weigh their DALYs differently? What about the quality of those years? I may be living a healthy life, but if I’m in an oppressive regime that doesn’t respect my personal or religious freedoms, should my DALYs be prioritized or deprioritized?

These questions often spill out on political stages, where liberals see the issue as a moral one that America is headed in the wrong direction on, and conservatives see wealth as the best way to reward those who contribute the most to prosperity or that a generous welfare state encourages laziness. The impasse here tends to stay in the moral liberal sphere (where we hear things like “this is who America is” or “we do not treat people like that”, and I’ve written about this too), but the data-driven reality is that inequality is bad for America.

The Path Forward

The clearest choice for reducing inequality is to invest in low-income children. Programs like the Earned Income Tax Credit and Child Tax Credit have been America’s most successful poverty alleviation programs, and these types of investments also make sense: children have the longest runway for seeing the gains of those investments and they also have some of the least leaky buckets when we look at the marginal value of public funds. The EITC and CTC were actually first proposed by Republican president Reagan and have long had strong bipartisan support ever since. Investments in children accomplish the moral, empirical, and data-driven strategies for reducing inequality.

Special thanks to David Deming for providing the inspiration for this piece.

INTERESTING ON THE WEB

📚 Who uses libraries and what role do people want them to play in society? Educated democrats who are more religious have a POV. Department of Data

📉 Obesity declines for the first time in decades in America. Ozempic and Wegovy may be the cause - FT (from the excellent John Burn-Murdoch)

🤲 Americans are more reliant than ever on government aid. Great maps. - WSJ

🧳 Why are we moving into disaster prone areas? Mapping net migration into and out of parts of the US - The NYTimes

Zillow introduces climate risk data into sales listings - First Street Foundation

🏆 A big congrats to my MIT advisor Simon Johnson, Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson on their Nobel Prize in Economics for their work on prosperity - MIT News

Love this piece.

As someone who became a parent a bit later than most, I have had more time than most new parents to think about the kind of world I would want to bring a child into.

Fortunately, during the years in which I delayed, wondering if I would ever be comfortable enough with the idea to go for it, I came across an economic ideology which gave me hope that we can actually fix the wealth gap. The more I read about it, the more I realized that economists across the political spectrum actually support such policies. Even partial implementations are so potent that places like Harrisburg, Pennsylvania have been able to renew their city, trigger a construction boom, attract investors, and ride out the dips in economic cycles.

It baffles me that with people so concerned about lack of housing, high inflation, and many other economic issues, few people invest the time toward better understanding how the economy works -- and end up voting for high tariffs instead. I mostly see this as a failure to make economists accountable for being able to accurately predict outcomes. This causes folks to lose faith in their credibility, and the study of economics in general.

All this is to say, we know how to fix our problems. These solutions have been around for a long time. We simply lack the will to implement them. And changing the lack of will, to me, is doable.

For anyone who wants to join me in mitigating the ever-increasing wealth gap, I welcome all the help we can get.

Too many were complacent during this last election cycle thinking someone else will do the work.

As a parent of a toddler, I know that time is fleeting. My kid will be grown before long and trying to navigate the economic system we've handed down. I can't afford to wait for someone else to take up the cause. Can you?